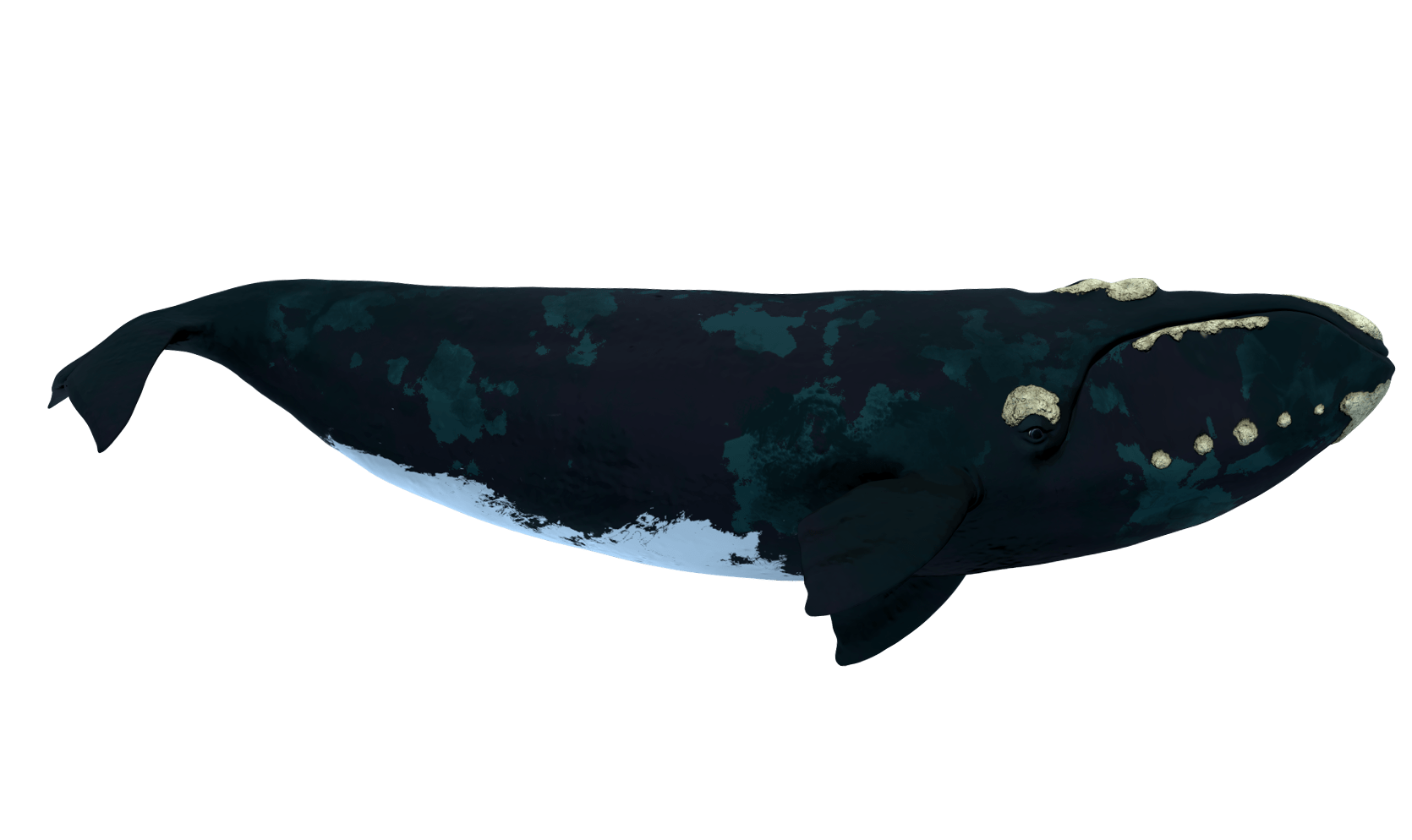

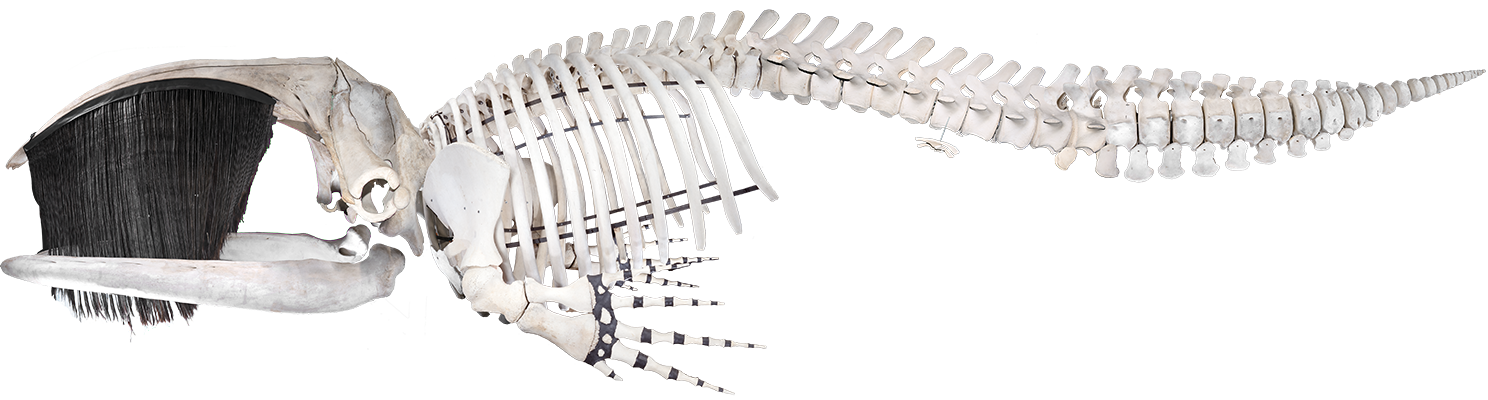

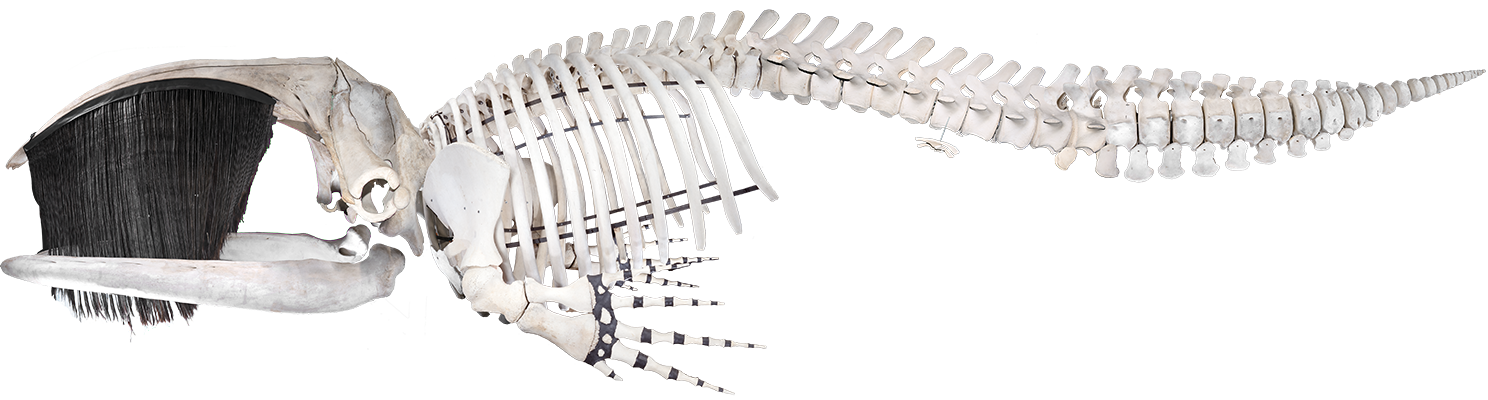

Right whales are plump, slow-swimming whales with a palate lined with long black baleen and a head covered with callosities!

Piper was first identified in January 1993 off the coast of Florida by the New England Aquarium. It is believed that she was 2 years old at the time.

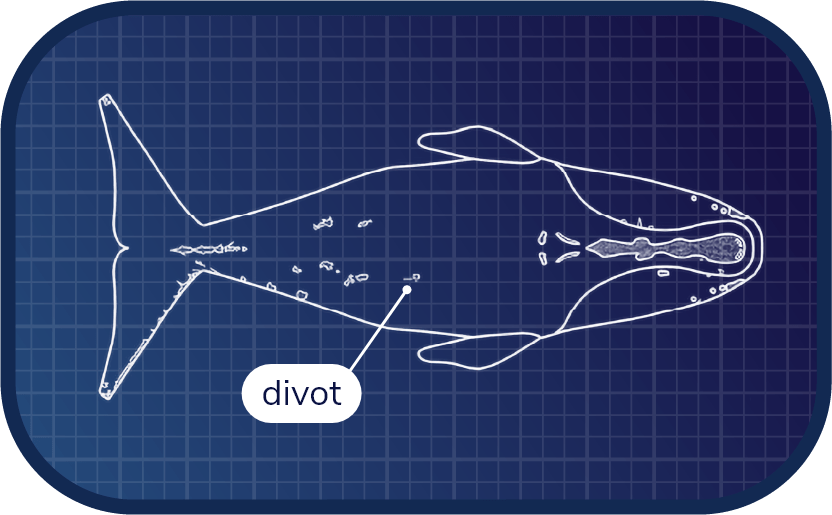

She can be recognized most notably by the white scars on her back and the shape of the callosities on her rostrum. Piper spends her winters off the east coast of the United States and summers in Nova Scotia’s Bay of Fundy. She has given birth to 3 calves in her lifetime: in 2006, 2009 and 2013.

Credits: New-England Aquarium

Piper’s back (right flank) photographed in 2003.

Credits: New-England Aquarium

Piper and her various identification marks. The “divot” indicated in the diagram corresponds to the hole-shaped scar that can be seen in the photo of Piper above. This scar was left by a satellite tag placed in August 2000 in the context of a study conducted by the University of Oregon aiming to better understand the population’s summer habitat. This tag stayed attached to Piper’s skin for approximately 126 days before falling off on its own.

On June 24, 2015, a right whale carcass is found drifting off the coast of Percé in Quebec’s Gaspé Peninsula. The carcass was towed to shore two days later so that it could be examined by veterinarians.

Unfortunately, the cause of mortality could not be determined, though we do know that it was not a collision or entanglement. The carcass was flensed, the bones were cleaned and the skeleton was reassembled for display at Tadoussac’s Marine Mammal Interpretation Centre.

Credits: baleine_noire/piper_remorquage_carcasse_GREMM.jpg

June 24, 2015: At 12:45 p.m., the Quebec Marine Mammal Emergency Response Network receives notice of a North Atlantic right whale carcass drifting between Bonaventure Island and Cap Blanc, near Percé. The hefty carcass is hauled to land, not without difficulty, and anchored at L’Anse-à-Beaufils. June 25, 2015: For 12 long hours, the crabbing boat Caroline H tows Piper to Newport.

Credits: GREMM

June 26, 2015: At 8 a.m., the whale is taken to port, where it is lifted out of the water with straps and placed on a flatbed truck three hours later. Then, the team faces a new challenge: the oversized pectoral fins won’t fit on the truck. To properly secure the whale, holes are drilled through its enormous pectoral fins. The vehicle then drives an hour and a half to a landfill in the municipality of Saint-Alphonse-de-Caplan, where it will be flensed and necropsied.

Credits: Steve Morin

June 27, 2015: The flensing team is made up of GREMM, Université de Montréal’s Faculty of Veterinary Medicine (directed by Stéphane Lair) as well as a number of volunteers. The animal’s state of decomposition is too advanced to determine the cause of death.

Credits: GREMM

June 28, 2015: After 20 hours of gruelling work by a team of 15, the flensing is finally completed late in the day. All the bones as well as the skull are loaded onto a dump truck, which will drive to the farm “Cinq Étoiles” in the municipality of Sacré-Cœur, near Tadoussac.

When Piper was found off the coast of the Gaspé Peninsula in 2015, it came as a big surprise. At the time, right whales foraged predominantly in the Bay of Fundy.

However, since 2017, they have abandoned this bay and have since been visiting the Gulf of St. Lawrence in greater numbers. Researchers believe that right whales’ prey must have changed habitat due to rising water temperatures, and the whales followed suit.

This map illustrates the range of the North Atlantic right whale as per pre-2015 observations. Yellow areas represent those parts of its range where the species is observed frequently, whereas blue areas show regions where observations are more rare. If current trends continue, the Gulf of St. Lawrence will become a high-frequency observation area.

Right whales owe their name to the whaling era, when they were considered the “right” whales to hunt.

Their slow-swimming nature made them easy targets and, once dead, they floated due to their thick layer of blubber. Even if they are now protected, their population has been decimated by whaling. Piper belongs to the last remaining population of North Atlantic right whales.

Credits: Charles d'Orbigny

Historic illustration of a right whale hunt.

Credits: Palme Production

When they die, right whales (like Piper, above) float on the surface due to their thick layer of blubber. Most whales sink and resurface only if putrefactive gases cause their bodies to bloat.

In addition to being slow and portly, a right whale like Piper is also distinguished by its spout. Instead of forming a column or a plume like the spouts of most species, the blast of a right whale is V-shaped.

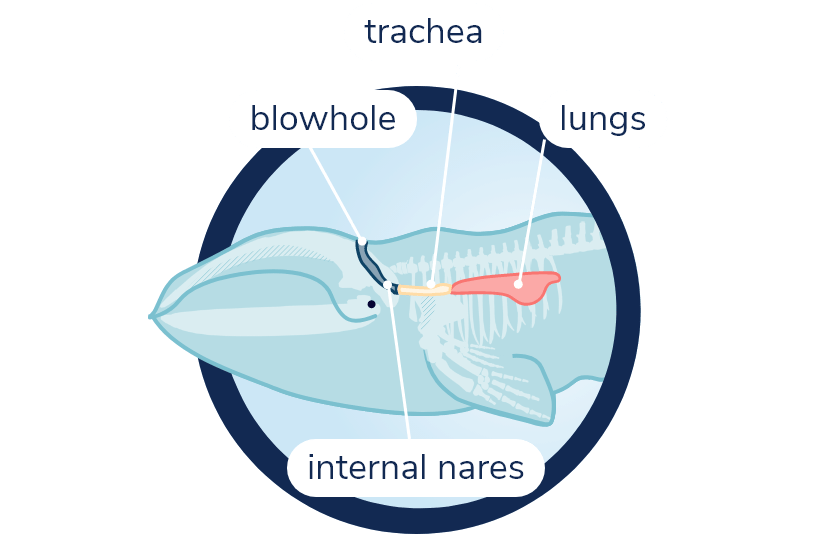

This is explained by the position of the species’ nostrils, or blowholes, which are located farther apart. The spout of a right whale can reach up to 5 m high. For large whales, this is often the first thing we see, and in clear weather blasts may be visible from up to several kilometres away.

Credits: GREMM

Typical V-shaped spout of a right whale.

How long do whales dive?

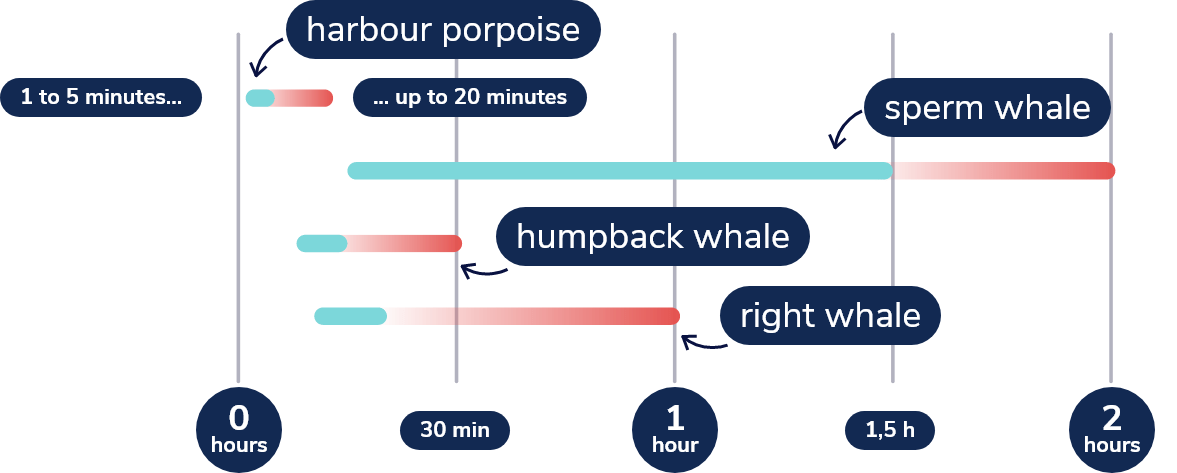

Not all whales have the same diving skills, but the duration of their dives is adapted to their lifestyle. A porpoise does not need to hold its breath as long as a sperm whale, which dives to great depths to find its prey. There is also a difference between a whale’s average dive time, illustrated by the blue bar in the graph, and its maximum endurance, shown in red.

How do Piper and other whales hold their breath for so long?

In fact, whales don’t actually have to “hold” their breath; rather they have to think to breath... A little like we have to remember to eat when we get hungry.

Rather convenient when over 80% of one’s time is spent under water! Whenever Piper wanted to breath, she had to contract her nostrils, which are naturally closed, so that air could pass through. This saved her from getting water up her nose!

Credits: NOAA/NMFS

Right whale with its nostrils (blowholes) in closed position.

Credits: NOAA

Right whale with its nostrils (blowholes) in opened position.

How do Piper and other whales manage to hold their breath for so long?

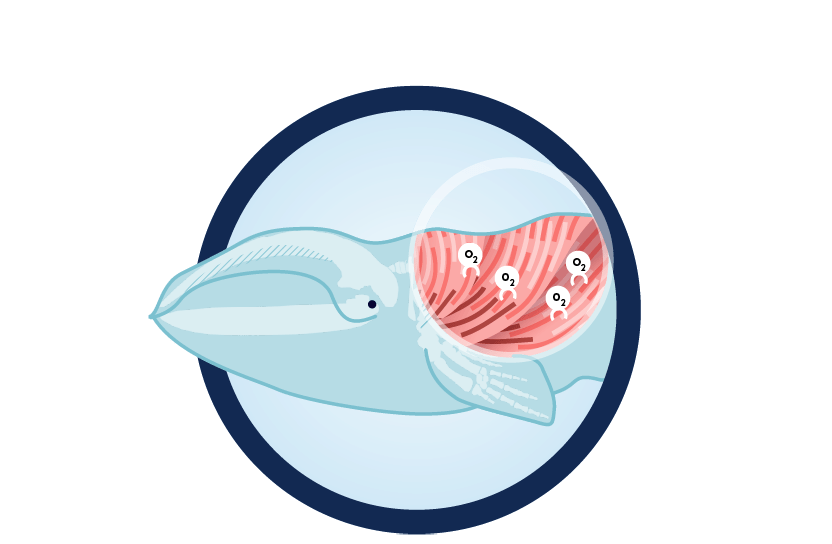

Humans exchange 13-14% of the air in our lungs with every breath we take, while a whale replenishes approximately 85%.

Perhaps surprisingly, whales do not breath more efficiently because they have enormous lungs. In fact, proportionally speaking, their lungs are even smaller than our own!

Where do whales keep their oxygen reserves when they dive?

Whales accumulate oxygen directly in their muscles thanks to a molecule called myoglobin.

This molecule is similar to hemoglobin, which is used to carry oxygen in the blood. This is why whales do not need bigger lungs, as this is not where they keep their oxygen reserves for diving... In any case, dragging along a big air pouch on deep dives doesn’t make much sense!

How do Piper and other whales ration their oxygen reserves?

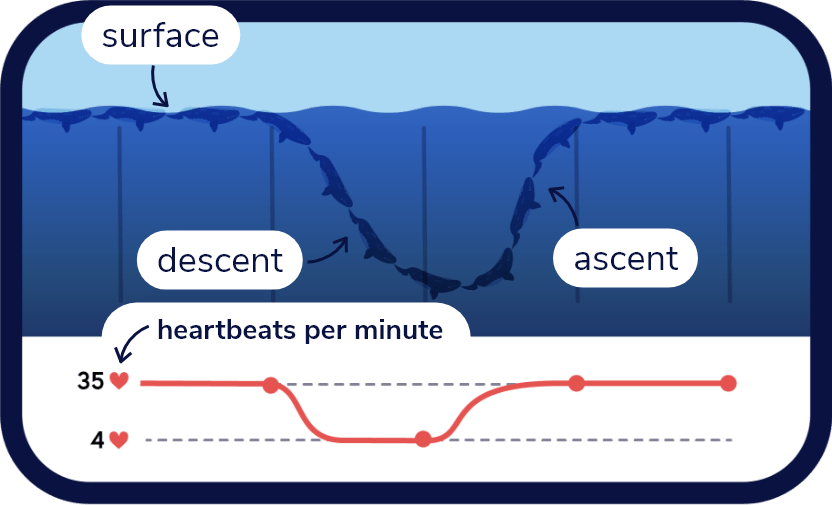

When a whale dives, its heart rate slows. This allows it to redistribute oxygenated blood from the heart to the other muscles that it needs to swim and capture its food.

When it resurfaces, its heart rate begins to accelerate again in order to circulate blood in the body, eliminate accumulated carbon dioxide and supply new oxygen.

The heart rate of a blue whale has already been measured. It can reach 30 to 37 beats a minute at the surface and fall to as low as 2 beats a minute when the animal dives. Researchers believe that the right whale might show a similar pattern. In comparison, a human heart rate ranges from 60 to 100 beats per minute.

When Piper forages in an area where fishing boats are operating, she runs the risk of getting herself enmeshed in ropes, nets or traps...

All around her, the jungle of rope in the water resembles a dangerous minefield. When one has no hands, getting oneself out of these fixes is complicated, and attempts to wiggle free can sometimes just make matters worse. Nutrient-rich sectors like the St. Lawrence River are hazardous, as they are just as attractive to whales as they are to fishermen.

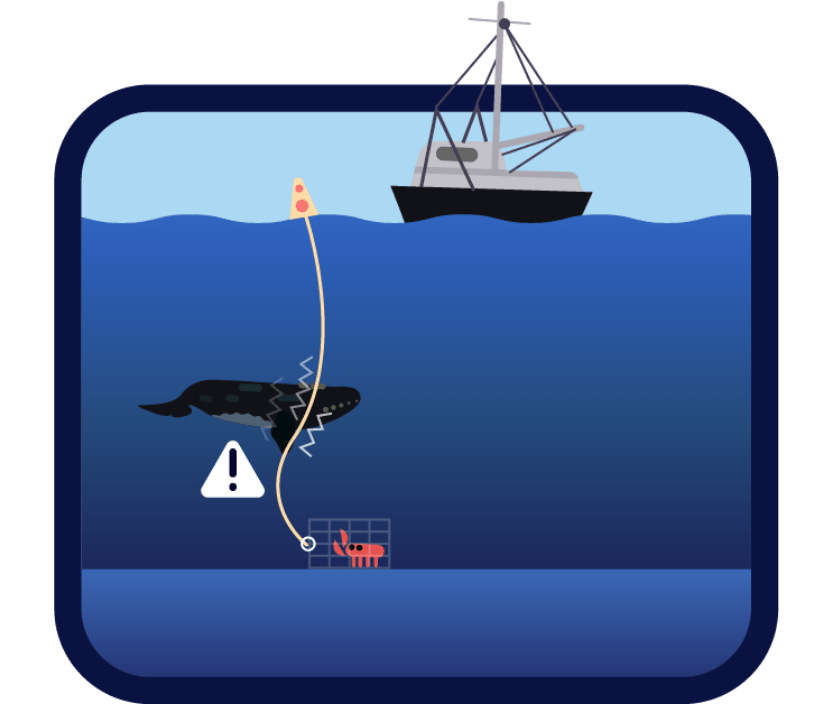

The rope tethering the buoys to the traps represents a risk of entanglement for right whales.

In the course of her lifetime, Piper got herself entangled on at least two occasions. And she’s not the only one! Over 85% of all right whales have already found themselves in this situation.

In her case, Piper was still able to swim despite the rope wrapped around her. The second time, in 2002, expert teams made several unsuccessful attempts to get her untangled. The rope finally unravelled on its own in 2006.

Credits: New England Aquarium

Photo of Piper taken in 2004 when she was still dragging the rope that had been encumbering her since 2002.

An entanglement can impair a whale’s ability to move, feed, reproduce and can even cause death.

Entanglements represent one of the main known causes of right whale mortality. This is also an issue for fishermen, who lose both their gear and their catch at the same time.

Credits: NOAA News Archive 123110

Entangled right whale

What can be done to lower the risk of entanglement?

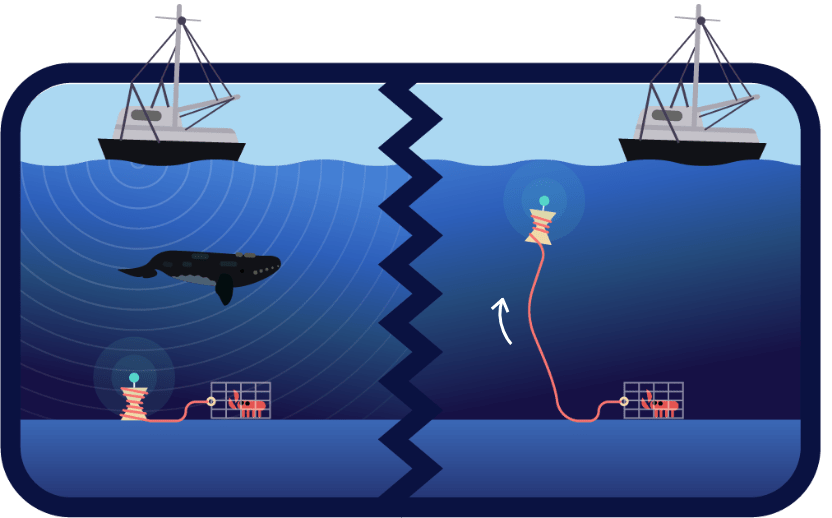

Use rope-less fishing gear

The current method used in the crabbing industry consists of tethering the traps – which sink to the seabed – to a buoy that floats on the surface. New techniques are being developed, including the use of submerged buoys that can be “called” to the surface only when fishermen need to recover them, meaning there is no rope lingering in the interim. However, this technology is costly and has not yet been perfected.

One solution to mitigate the risk of entanglement in rope connecting buoys to traps is to keep the buoys on the seabed and to be able to bring them up only as needed.

What can be done to lower the risk of entanglement?

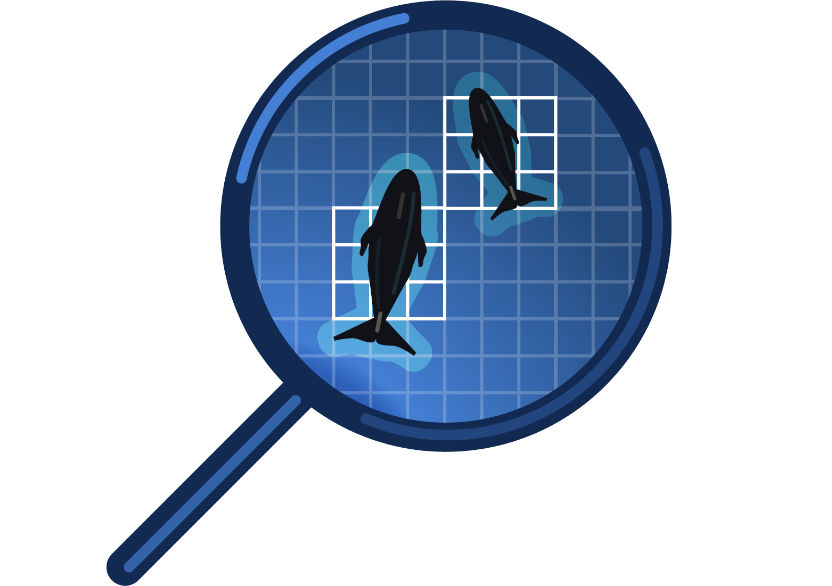

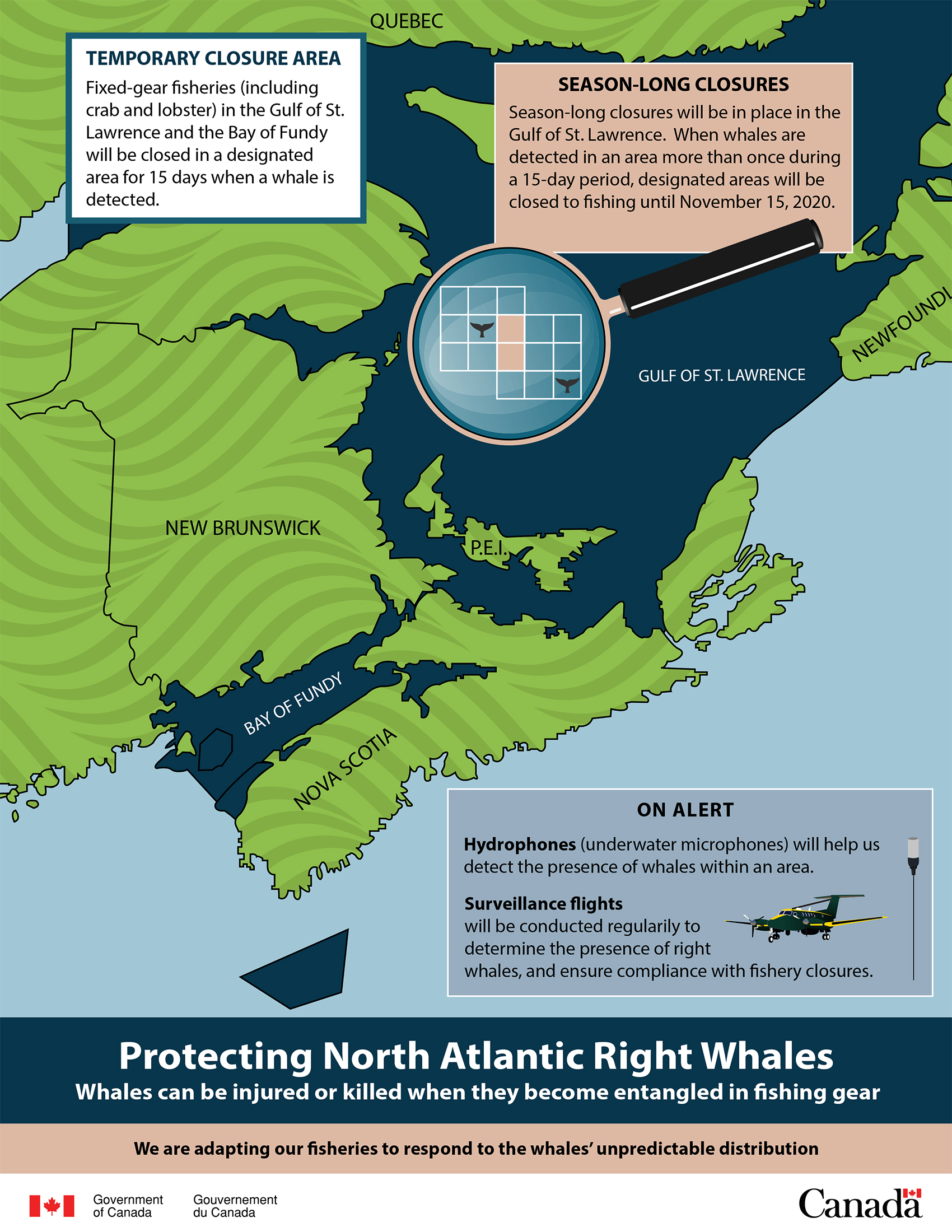

Refrain from deploying fishing gear in areas that are heavily used by whales.

This helps minimize the chances that a whale will come into contact with the rope. But determining which areas to close, when and for how long cannot be done randomly! Regular monitoring to gauge the presence of whales is an essential decision-making tool.

Overview of the Government of Canada’s fishing zone management measures for 2020.

Use rope-less fishing gear

Refrain from deploying fishing gear in areas that are heavily used by whales.

Educating oneself on the origins of the product and how it was harvested will encourage better practices and will be beneficial not only for right whales but for marine wildlife in general. Ask for certified products.

Now that you’ve heard Piper’s story, let’s go meet the other whales!

North Atlantic Right Whale

Eubalaena glacialis

Characteristics

North Atlantic right whales

Weight

30 to 70 tons

Length

13 to 17 m

Lifespan

Probably over 70 years

Population

approx. 356 individuals

Status

Endangered

Piper

Weight

34.6 tons

Length

13.9 m

Birth - Death

1991 (estimated) - June 2015

ID number

2320

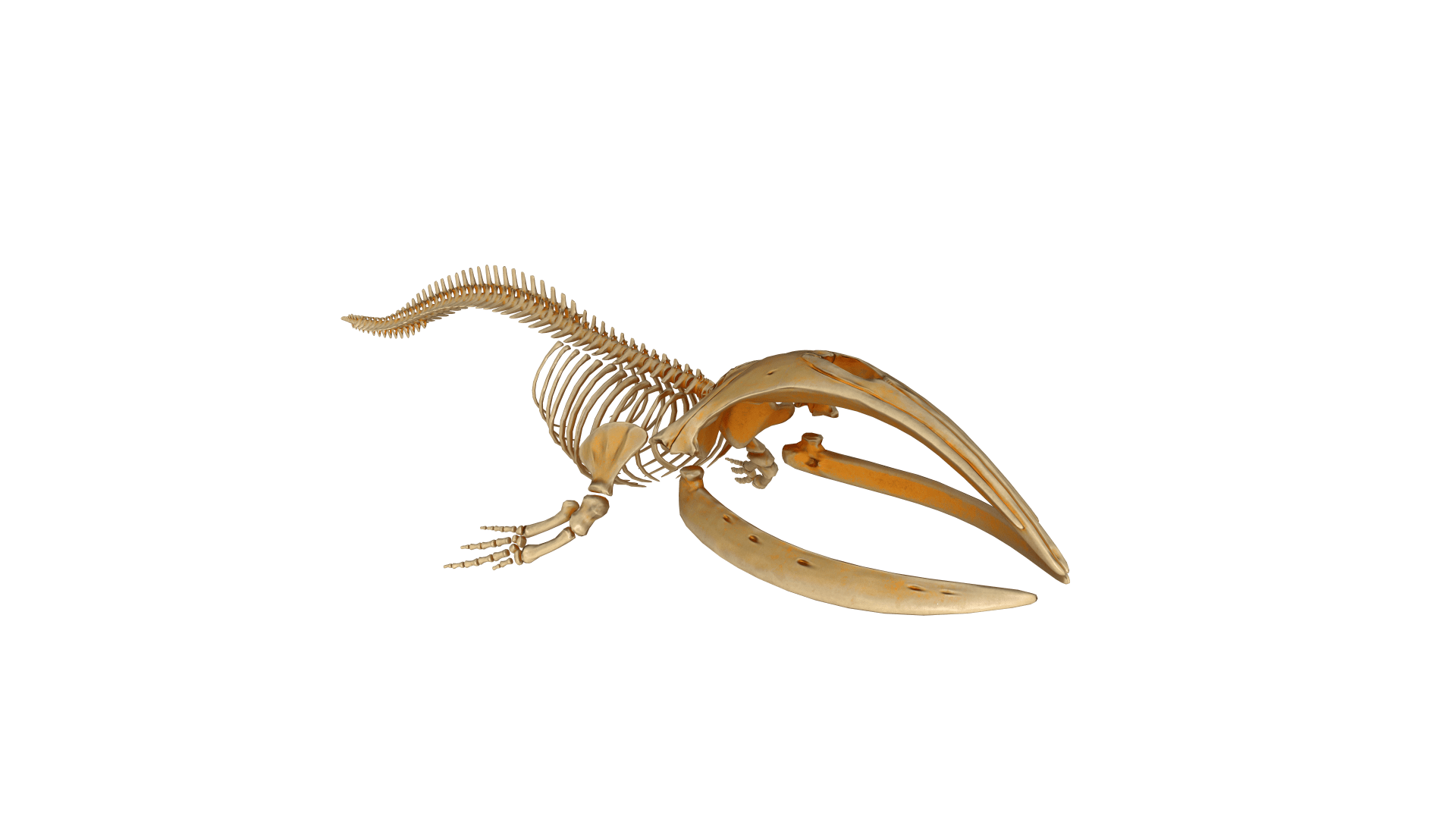

Sex

Female

Photo of Piper’s skeleton. In its mouth is a giant set of baleen. This North Atlantic right whale skeleton is on display at the Marine Mammal Interpretation Centre in Tadoussac.

North Atlantic Right Whale

Eubalaena glacialis

Characteristics

North Atlantic right whales

Weight

30 to 70 tons

Length

13 to 17 m

Lifespan

Probably over 70 years

Population

approx. 356 individuals

Status

Endangered

Piper

Weight

34.6 tons

Length

13.9 m

Birth - Death

1991 (estimated) - June 2015

ID number

2320

Sex

Female

Photo of Piper’s skeleton. In its mouth is a giant set of baleen. This North Atlantic right whale skeleton is on display at the Marine Mammal Interpretation Centre in Tadoussac.