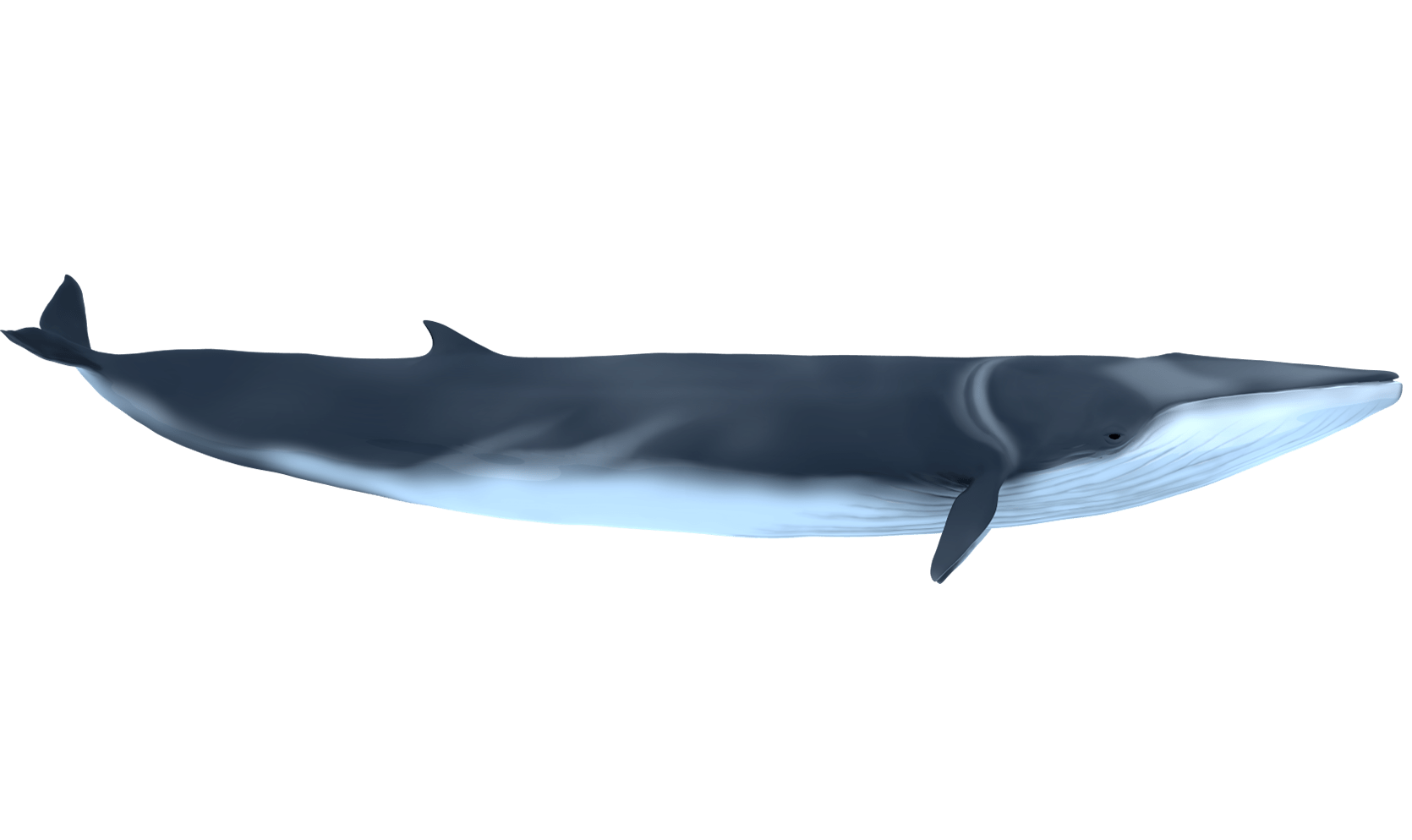

Fin whales like Bergeronnes feature a number of unusual characteristics!

Prior to the discovery of its carcass, Bergeronnes was not known to researchers. This individual may have previously visited the St. Lawrence, but it had never been formally identified. Judging by its size – 16 m long – Bergeronnes was a 1- or 2-year-old juvenile.

Below are 3 known fin whales in the St. Lawrence Estuary (Caïman, Zipper and Piton). Can you notice any differences between these individuals? Take note of the shape of the dorsal fin, the presence of scars...

Credits: GREMM

Caïman

Credits: GREMM

Zipper

Credits: GREMM

Piton

Identifying this type of whale is no easy task. To do so, we examine the shape of the fin and any scars the animal might have, in addition to trying to photograph the chevron. This lighter colour pattern behind the blowhole is like a fingerprint, unique to each individual.

Credits: GREMM

On the backs of the two fin whales closest to the viewer, we can see markings that are lighter in colour. This pattern is called the chevron, and is particularly apparent on the right side. Do you notice any differences between the patterns of these two individuals?

On September 17, 2008, a dead fin whale was found drifting off the coast Tadoussac. Is it merely happenstance that, one month earlier, there was a red tide in the St. Lawrence?

Everything suggests that the whale was intoxicated by this algal bloom. Indeed, traces of the toxin were found in Bergeronnes’s liver, which was able to be examined because the carcass had been towed to Les Bergeronnes for study and to recover and preserve the skeleton.

Credits: GREMM

The carcass of Bergeronnes drifts off the coast of Tadoussac. Putrefactive gases cause its belly to swell and its body to float.

Credits: GREMM

Bergeronnes owes its name to the village where its carcass was hoisted out of the water.

Credits: GREMM

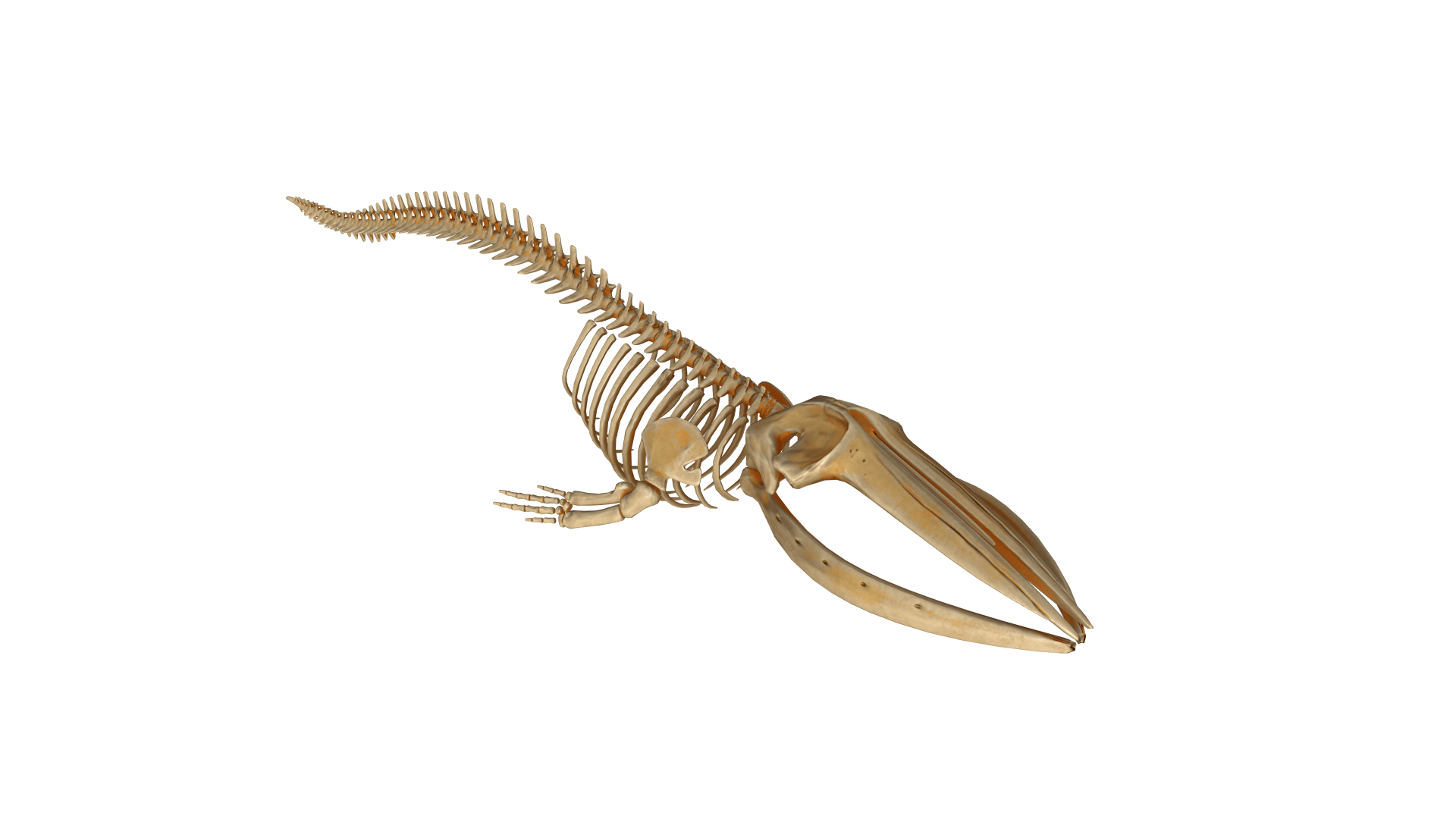

Bergeronnes’s carcass was taken to a field for flensing with a view to preserving its skeleton. It took several volunteers to remove all the flesh from the bones.

Like all fin whales, Bergeronnes had asymmetrical colouring, which, in the animal kingdom, is quite unique! This species has a light side and a dark side...

The right side is always lightest: the baleen is pale, the jaw is white and the chevron is more distinct. Conversely, the left side is darker, with dark baleen and a grey jaw. One theory is that the colour contrast might give the animal extra camouflage when it swims on its side to catch its prey. This has never been proven, however.

Credits: Robert Gailbraith

The demarcation between the light side and the dark side is quite conspicuous below the jawline.

Bergeronnes was in a good physical condition when his carcass was discovered, so at least we know he was getting enough to eat... Did he mostly feed on his own or did he ever team up with other fin whales?

These whales sometimes join forces with other individuals to improve their chances of a successful hunt. They swim in coordinated fashion by making circles in order to herd their prey. These associations are temporary, however, and are not characterized by complex social interactions like we might observe in dolphins or belugas. Fin whales are also often seen alone.

Credits: GREMM

Off the coast of Tadoussac in the St. Lawrence Estuary, while it is not unusual to see fin whales group together as seen in this photo, they are also often observed alone.

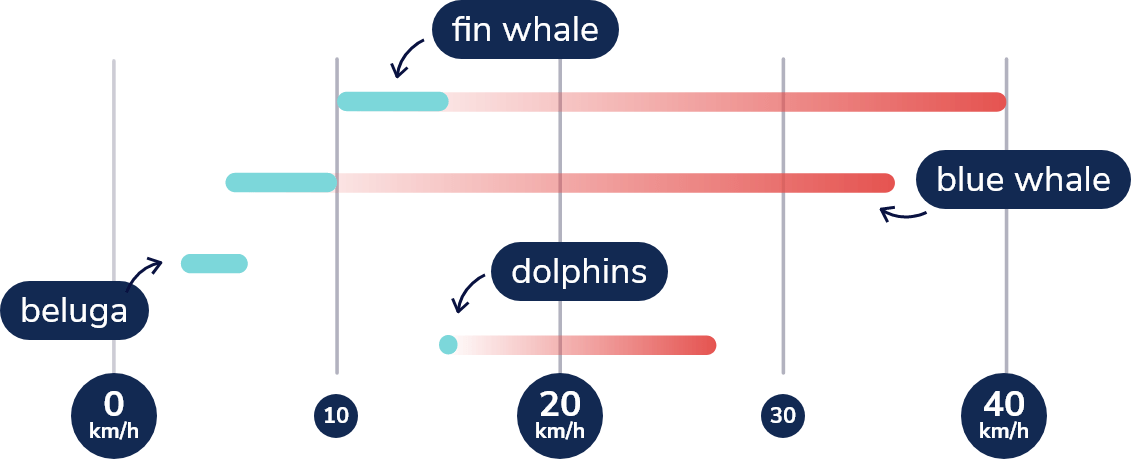

Capable of reaching top speeds of 40 km/h, fin whales are known as “greyhounds of the sea”.

However, although Bergeronnes would probably have earned an A+ in athletics for his speed, he would have received poor marks in gymnastics. Fin whales are generally not the greatest of acrobats, as it is quite rare to see them breach.

Credits: GREMM

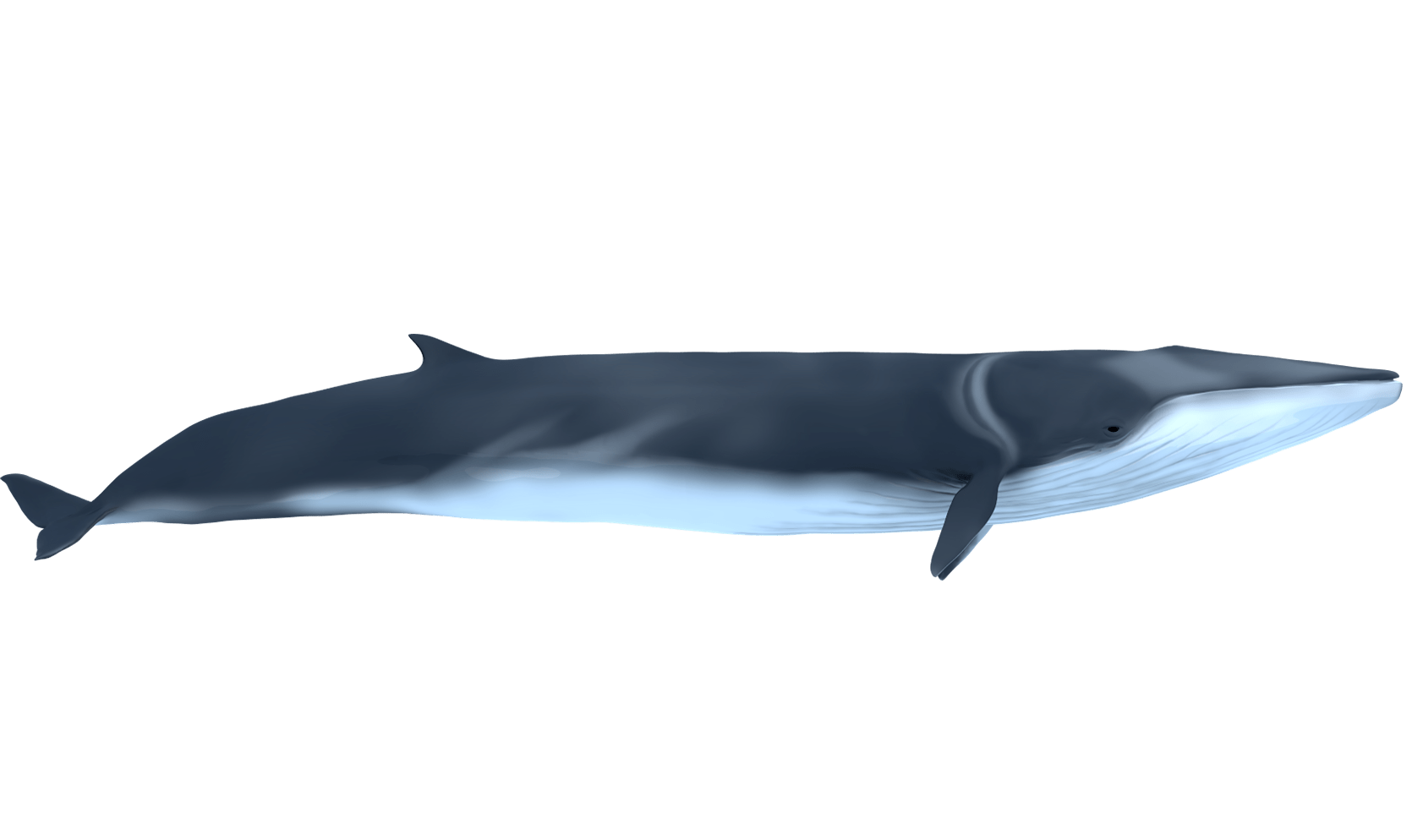

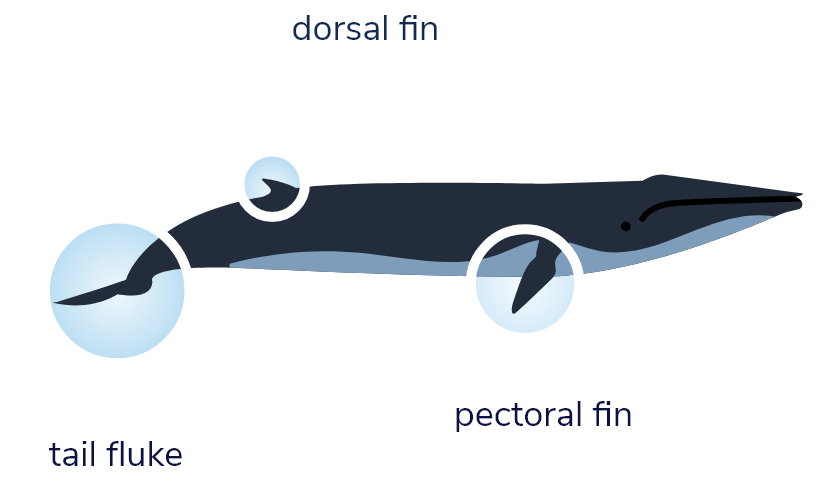

With their smooth skin and hydrodynamic profile, whales like Bergeronnes glide easily through the water. For thrust, these animals use powerful movements of the tail, which are just as effective on the ascent as on the descent.

Their pectoral fins are not used for propelling themselves like human swimmers might do with their arms, but rather for manoeuvring under water. These fins are also used for stability, as is the dorsal fin, which acts like a skeg on a boat, preventing the animal from rolling onto its side.

How fast do whales swim?

Swimming speeds vary from one species to another, with belugas being rather slow in comparison to dolphins or fin whales. There is also a difference between a species’ typical swimming speed (illustrated by the blue bar) and its top speed (illustrated by the red bar). Likewise, humans don’t run as fast as they walk!

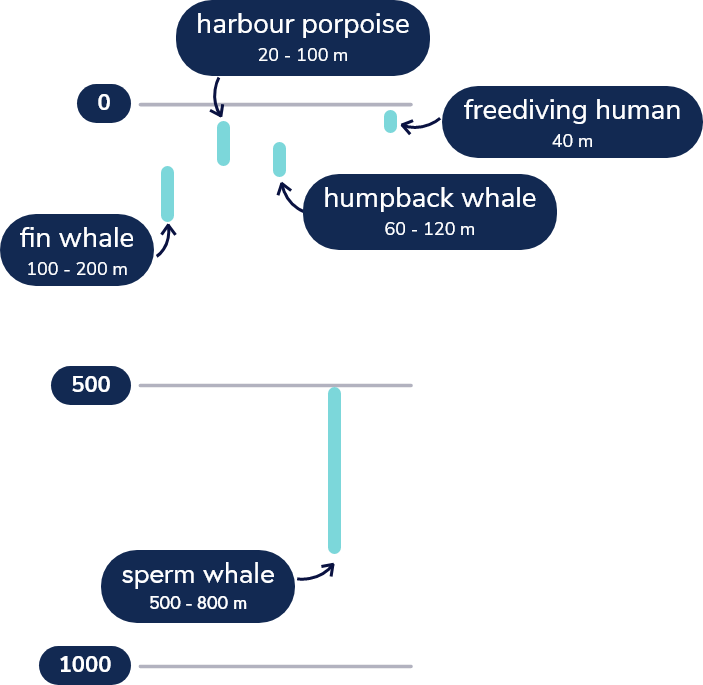

How deep do whales dive?

Whales do not all dive to the same depth. In general, they dive to where they will find their food. For a fin whale, an average dive is between 100-200 m, but if it can find its food near the surface, it won’t go any deeper. Similarly, the main prey of the sperm whale are usually found at depths of between 500 and 800 m, though the species can descend as deep as 2,000 m to find its meal if it needs to.

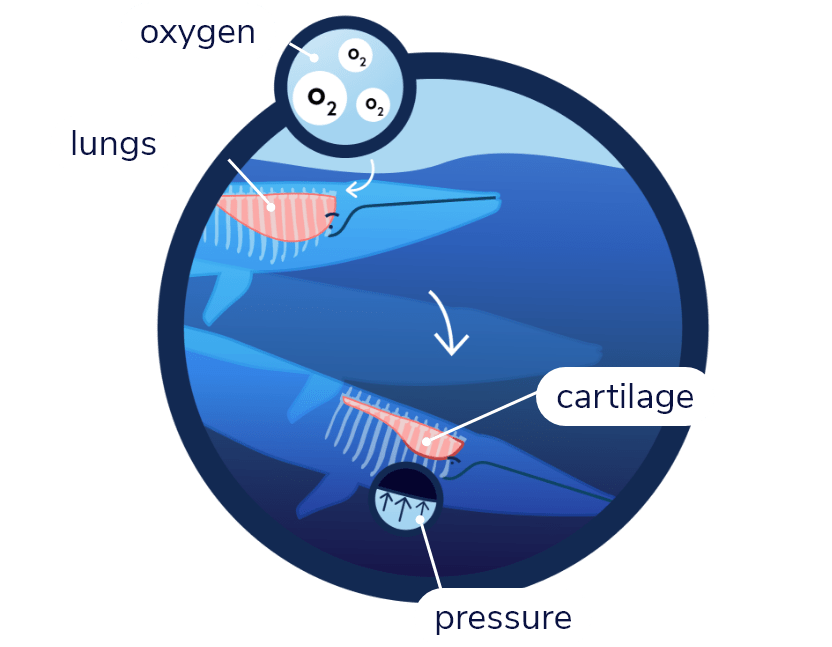

How do whales withstand the pressure associated with deep water?

Thanks to the cartilage that protects the upper part of their lungs and the absence of air cavities such as facial sinuses and outer ears.

The deeper one dives, the greater the pressure. Air cavities like the lungs therefore risk being crushed under this pressure. Whales overcome this issue with cartilage, which strengthens the upper part of their lungs. So, while the lower part of the lung collapses, the upper part retains its shape, helping the whale in its ascent. Also, in humans (and other land mammals), the sinuses in our nose and the air chambers in our ears are a potential problem… But whales have neither facial sinuses nor external ears. Problem solved!

Can whales have diving accidents?

Generally speaking, whales know how to manage their ascents in order to avoid this issue. That said, such an incident could occur if the animal is stressed and comes up too quickly. In such a scenario, the whale could indeed suffer decompression sickness.

It is a well known phenomenon in human divers. Dissolved nitrogen microbubbles in the blood and the body’s tissues expand if the diver ascends too quickly, and the gas cannot be exhaled through the lungs. This can result in lesions, which in turn can lead to joint pain, paralysis, or even death.

Credits: GREMM

A fin whale comes to the surface to breathe.

Whales are capable of hearing an approaching ship. But when they swim in a high-traffic boating or shipping area, they may end up growing acclimated to the noise and not paying as much attention.

In a busy shipping channel like the St. Lawrence, there is therefore a greater risk of collisions. Additionally, these ships are not equipped with sonars that could be used to detect whales.

Credits: GREMM

For large vessels and their crews, a collision with a whale will go largely unnoticed. For the animal, however, ship strikes can cause injury or even death.

In the case of Bergeronnes, it is not possible to rule out a collision as the cause of mortality. He appeared to have signs of bleeding on his back, but the severity of the injury remains unclear. Several fractured bones were found, but since they were not associated with the bleeding, it is believed that this damage occurred after the animal died. Pinpointing the exact cause of death is often difficult...

Credits: GREMM

It is possible that the bones of Bergeronnes were damaged during transport. Although the risk of collision with ships is known to be a threat to these whales, one must always be careful not to jump to conclusions too quickly.

Credits: GREMM

This scar is how this female fin whale got her nickname. When she was first identified in 1994, Zipper had fresh wounds. Her tattered skin showed signs of a run-in with a boat propeller. Luckily for Zipper, she survived her injuries and is still a regular visitor to the St. Lawrence.

Atlantic fin whales such as Bergeronnes have “special concern” status. They are mainly threatened by issues related to maritime traffic, including ship strikes.

Whales may be giants, but they are no match for a large vessel. A fin whale is about the size of 1 or 2 containers, while this type of ship carries thousands of containers.

Credits: GREMM

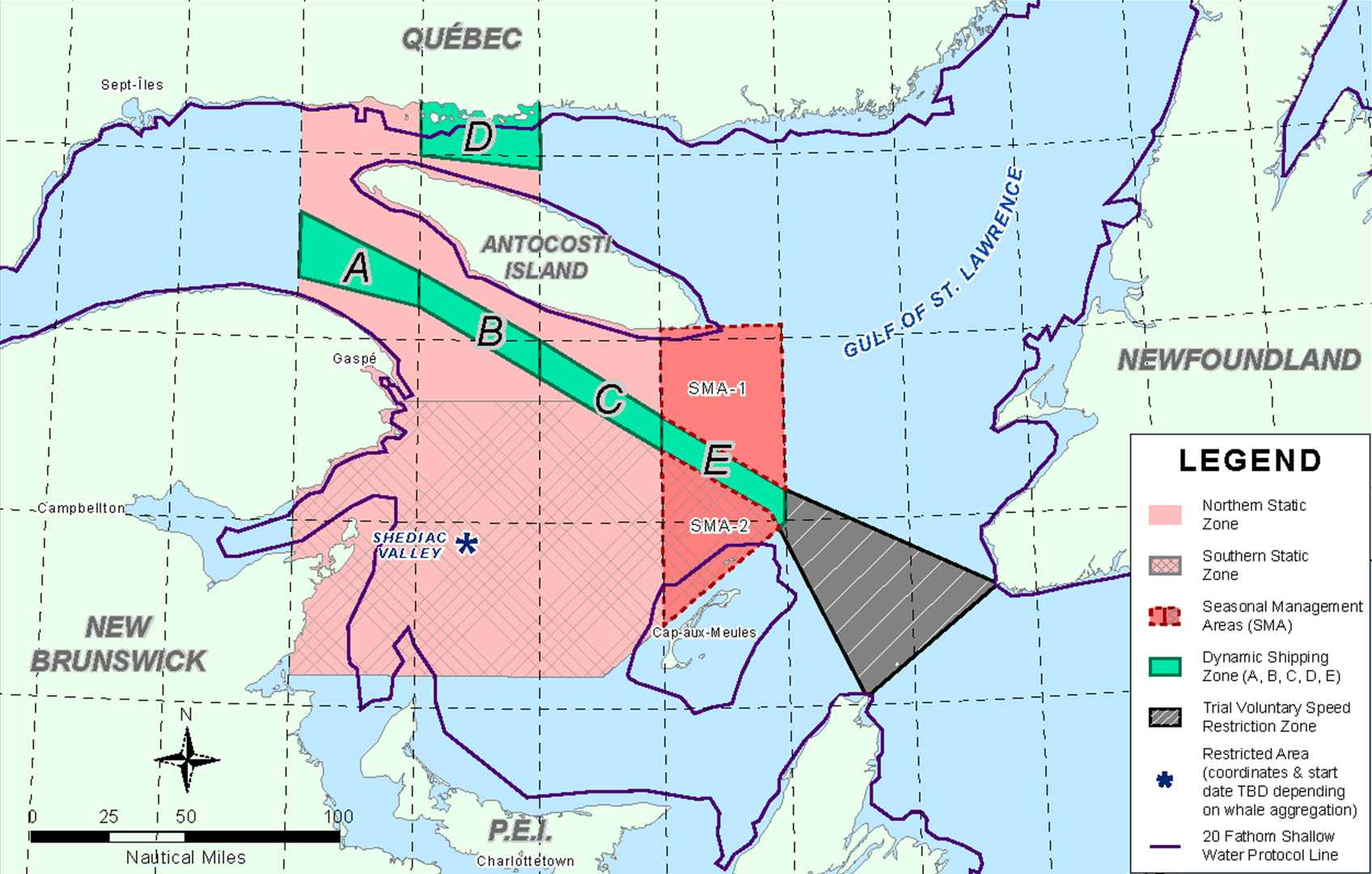

What can be done to reduce collisions ?

Simply slowing down lowers the level of risk.

A slower-moving boat is more likely to spot a whale in time and/or give the animal a chance to swim away. At lower speeds, the risk of a fatal collision is also greatly reduced.

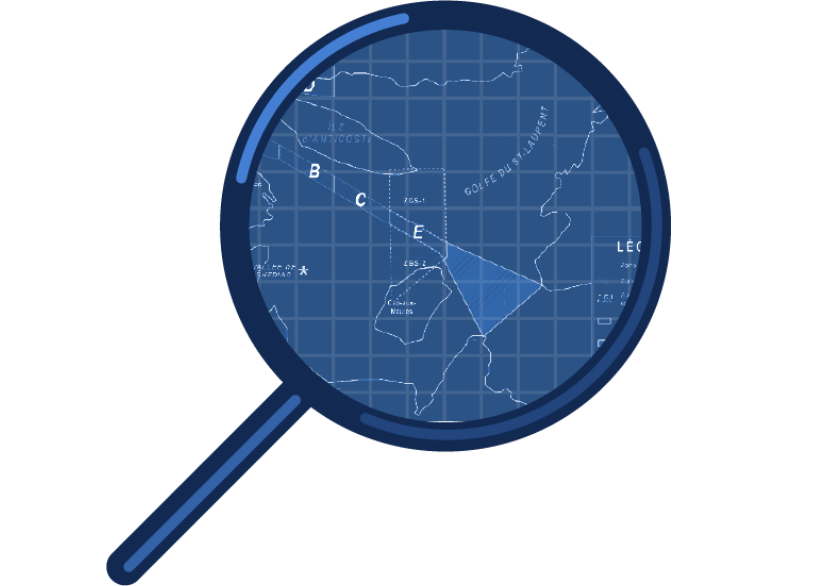

Credits: Transport Canada, Government of Canada

Map of 2020 speed restriction measures in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. In static areas (pink), all vessels over 13 m long must respect a speed limit of 10 knots. In the dynamic corridor (green), speed restrictions only apply when there is a detection of a North Atlantic right whale, a species particularly vulnerable to collisions.

What can be done to reduce collisions ?

Stay alert and adapt your boating to the presence of whales.

Having trained observers on board increases the chances of spotting whales in time. And, once you know the areas where whales are most prevalent, you can avoid these areas in order to lower the chances of crossing their paths.

Credits: GREMM

Did the crew onboard spot the humback whale ahead?

Now that you’ve heard Bergeronnes’s story, let’s go meet the other whales!

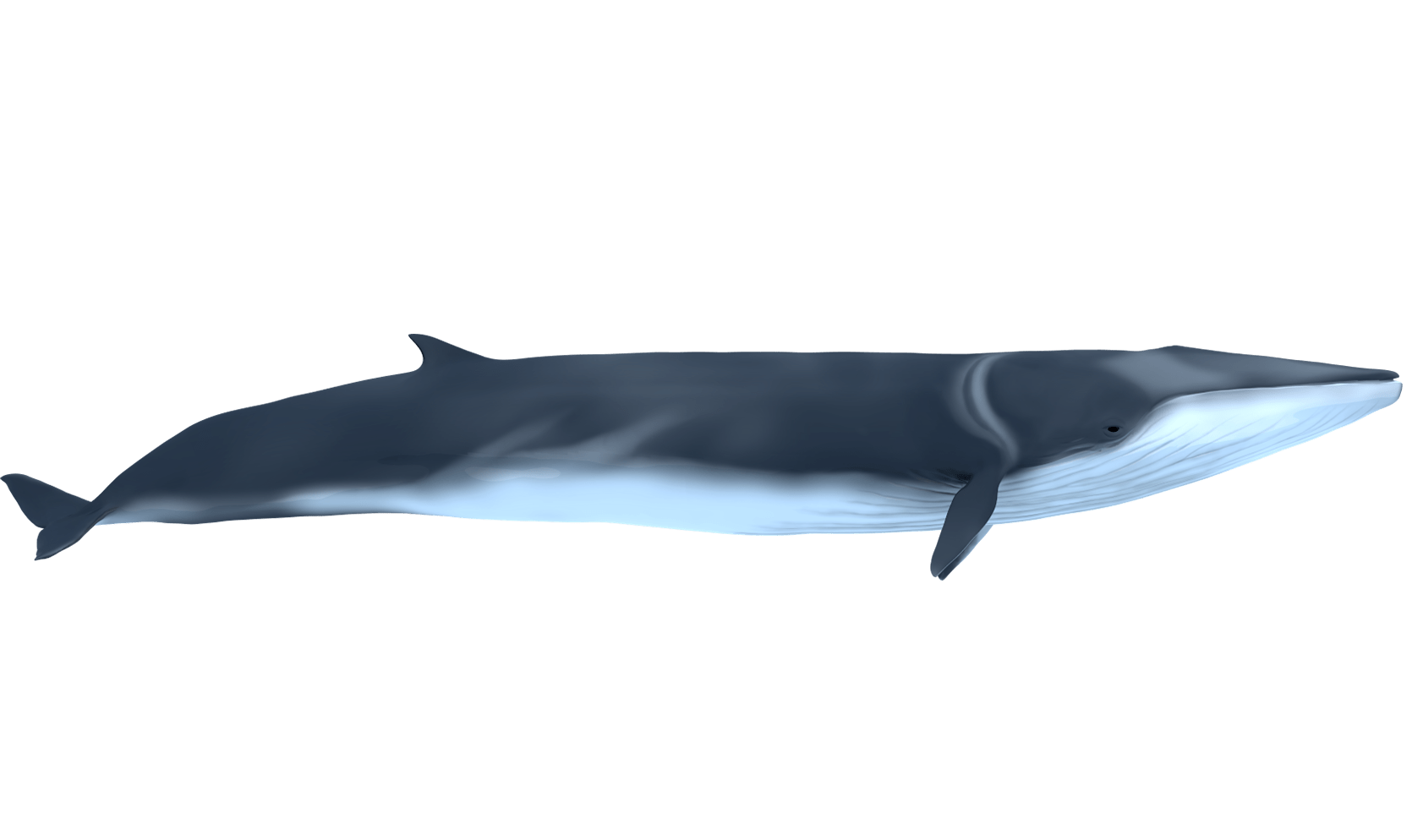

Fin Whale

Balaenoptera physalus

Characteristics

Fin whales of Eastern Canada

Weight

40 to 50 tons

Length

18 to 20 m, up to 25 m

Lifespan

80 to 100 years

Population

approximately 7,400 individuals

Status

Special concern

Bergeronnes

Weight

unknown

Length

16.24 m

Birth - Death

possibly between 2006 and 2007 - September 2008

ID number

not known to researchers

Sex

Male

After lying in a field for over a decade, the bones of Bergeronnes were pieced back together to reassemble its skeleton. The latter is now on display in a new dedicated exhibition hall at the Marine Mammal Interpretation Centre in Tadoussac. A number of bones had been damaged along the way, so painstaking efforts were required to restore the skeleton to its full lustre.

Fin Whale

Balaenoptera physalus

Characteristics

Fin whales of Eastern Canada

Weight

40 to 50 tons

Length

18 to 20 m, up to 25 m

Lifespan

80 to 100 years

Population

approximately 7,400 individuals

Status

Special concern

Bergeronnes

Weight

unknown

Length

16.24 m

Birth - Death

possibly between 2006 and 2007 - September 2008

ID number

not known to researchers

Sex

Male

After lying in a field for over a decade, the bones of Bergeronnes were pieced back together to reassemble its skeleton. The latter is now on display in a new dedicated exhibition hall at the Marine Mammal Interpretation Centre in Tadoussac. A number of bones had been damaged along the way, so painstaking efforts were required to restore the skeleton to its full lustre.