Coastal cetaceans, harbour porpoises visit the St. Lawrence by the thousands.

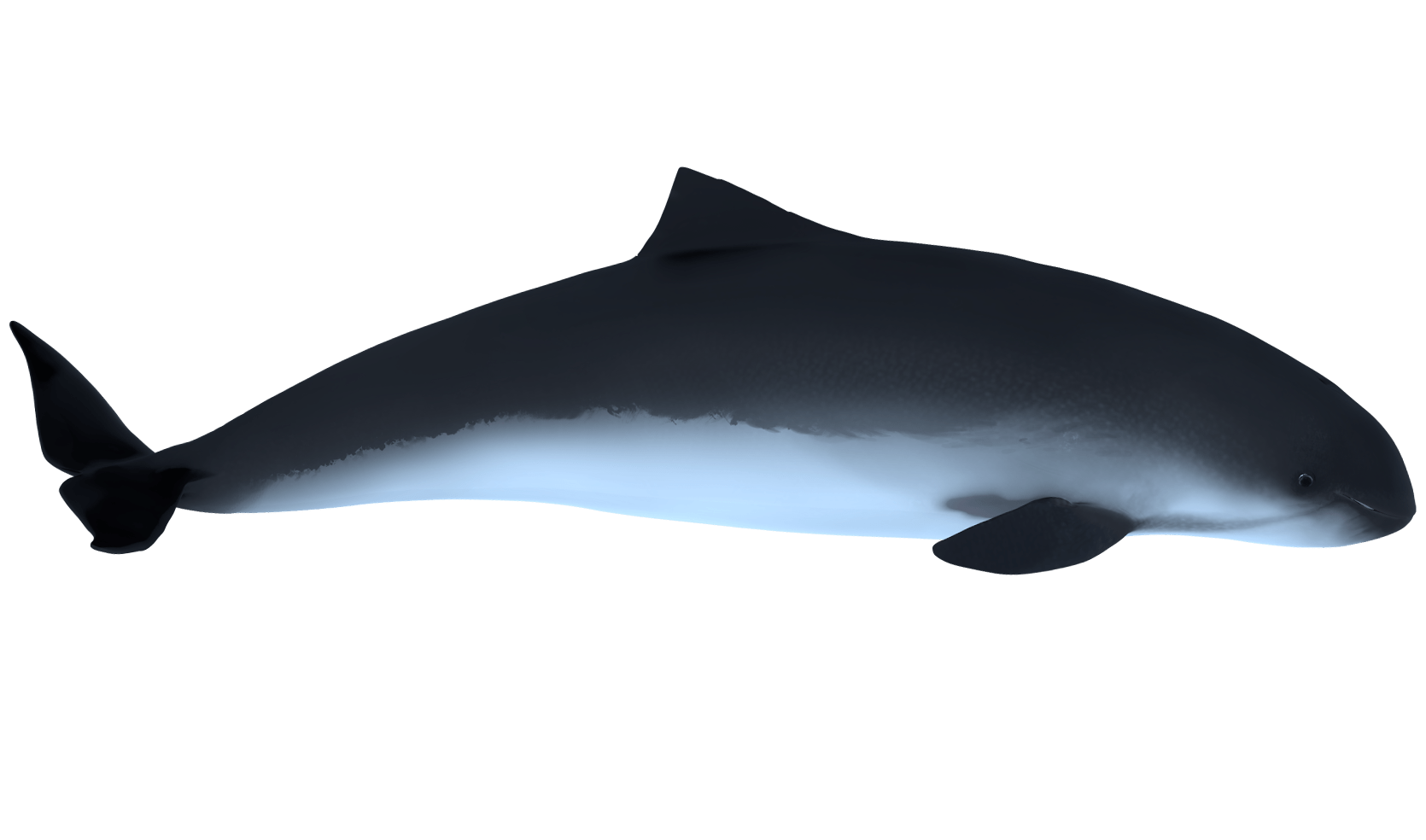

Laurent was one of the first occupants of the Marine Mammal Interpretation Centre. Not much is known about this individual, however. Indeed, there is no identification catalogue for harbour porpoises in the St. Lawrence. As a result, very little is known about the life histories of individuals like Laurent.

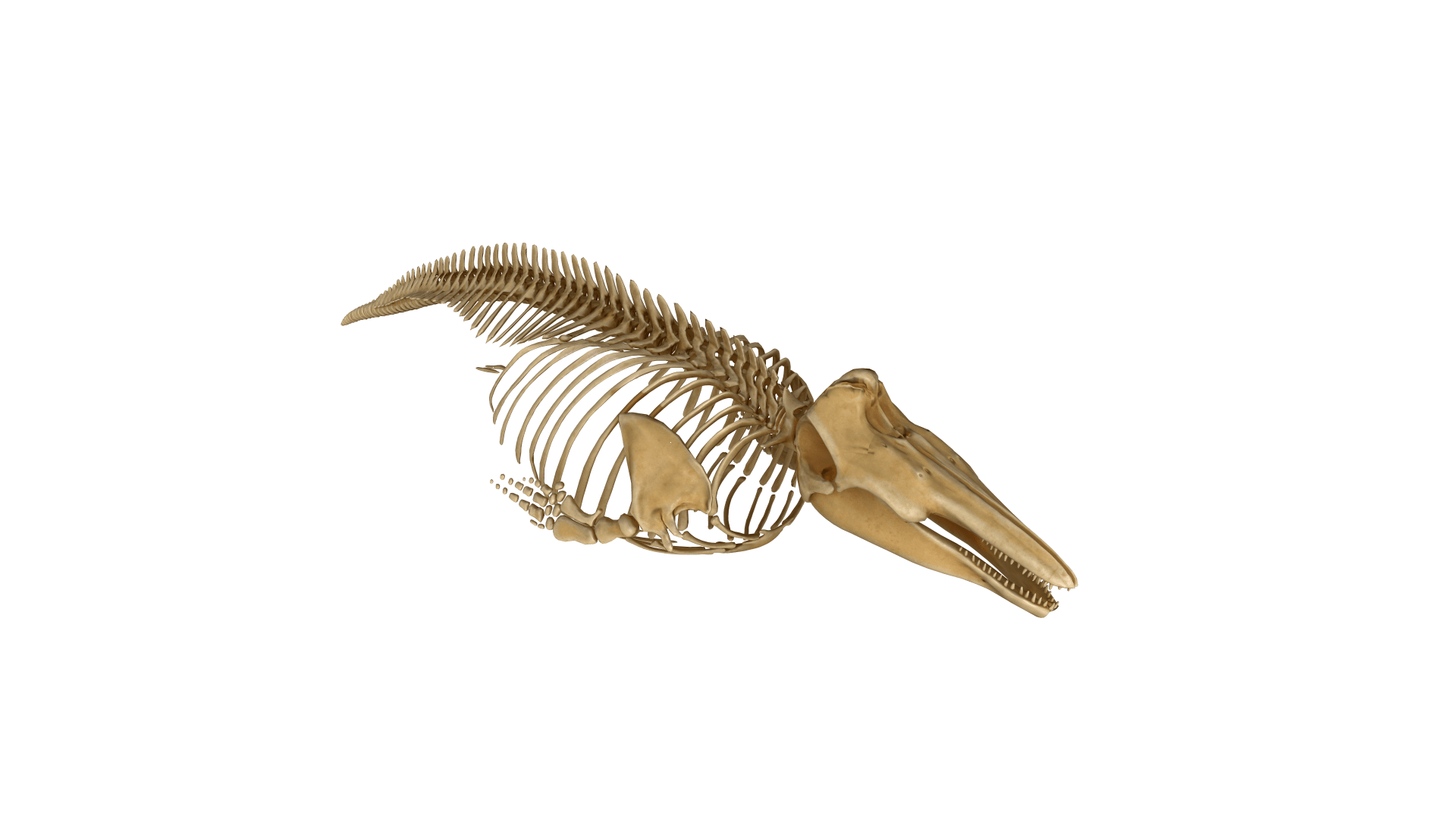

We know very little about Laurent’s death. Judging by the size of its skeleton, we do know that it was less than a year old.

Its carcass was recovered in the late 1980s somewhere on the shores of the St. Lawrence, but information regarding the exact location of its discovery and even the size and sex of the animal has been lost.

Credits: GREMM

This is Laurent’s carcass, but this is not the location where it was found. This photo was staged on the rocks adjacent to the Marine Mammal Interpretation Centre in Tadoussac, where the carcass was brought to display its skeleton in an exhibition.

Less than one year old when it died, Laurent was probably still dependent on its mother’s milk. Even though she was still nursing her calf, Laurent’s mother may have been carrying another baby porpoise in her belly.

The porpoise is one of the few cetaceans that can give birth every year and therefore become pregnant even if still lactating. That takes a lot of energy!

Credits: GREMM

An adult porpoise and a smaller individual swim side by side. It may be a mother and her calf.

Male porpoises also lead intense lives. Although they are about the same size as a human, harbour porpoises have reproductive organs on an entirely different scale! A porpoise’s penis is approximately 50 cm long and its testicles account for about 5% of its weight.

This means that if a 70 kg man were endowed with porpoise testicles, they would weigh 3.5 kg! That’s the average weight of a watermelon... During the breeding season, male porpoises do not fight with one another, but they do try to mate with as many females as possible. This is known as sperm competition.

Credits: Ecomare/Sytske Dijksen

Male harbour porpoise with erect penis.

Porpoises are often mistaken for dolphins, but these animals represent two distinct families of cetaceans. There are tricks to telling them apart at sea, but they can also be distinguished by examining their teeth.

Porpoises are often mistaken for dolphins, but these animals represent two distinct families of cetaceans. There are tricks to telling them apart at sea, but they can also be distinguished by examining their teeth.

Credits: GREMM

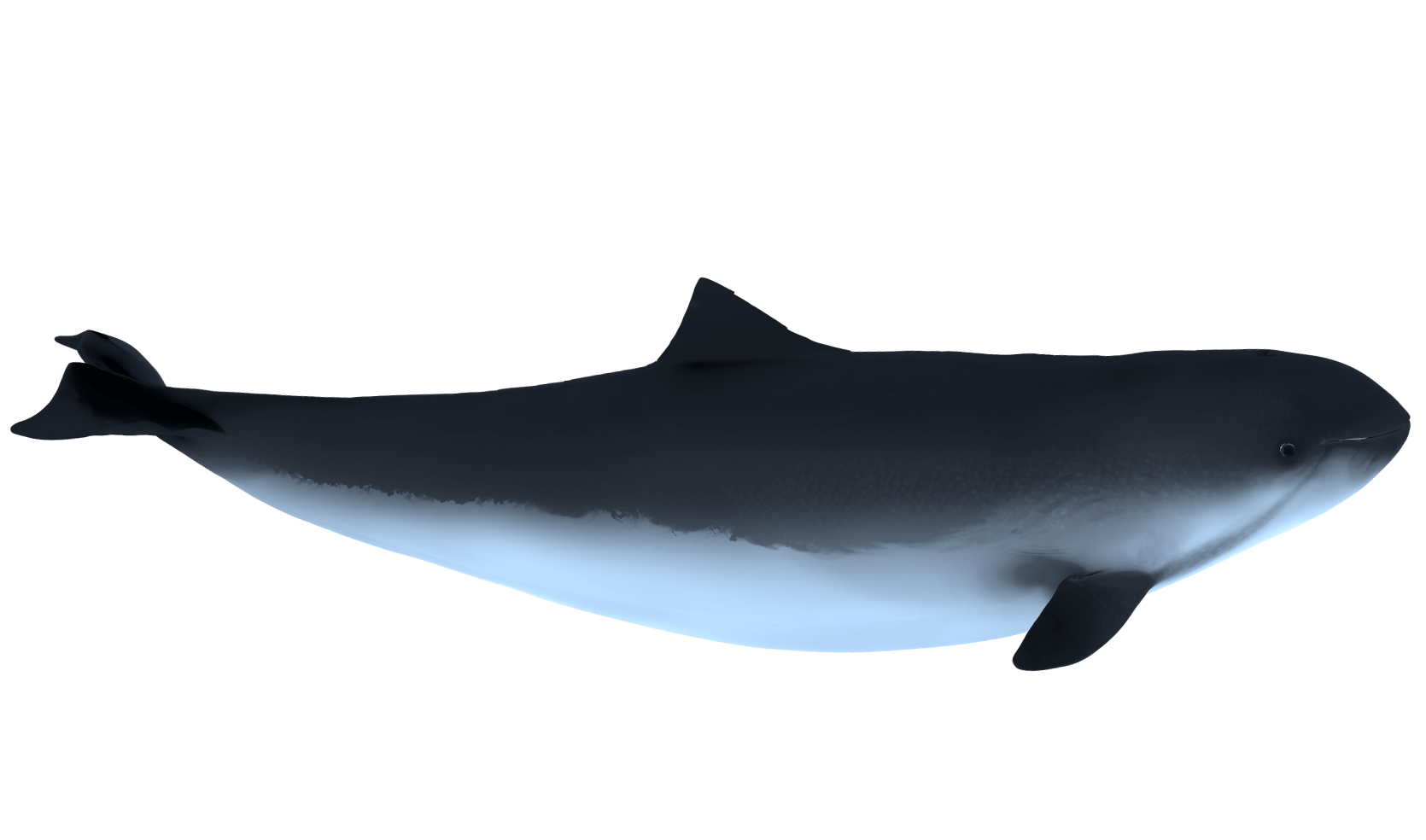

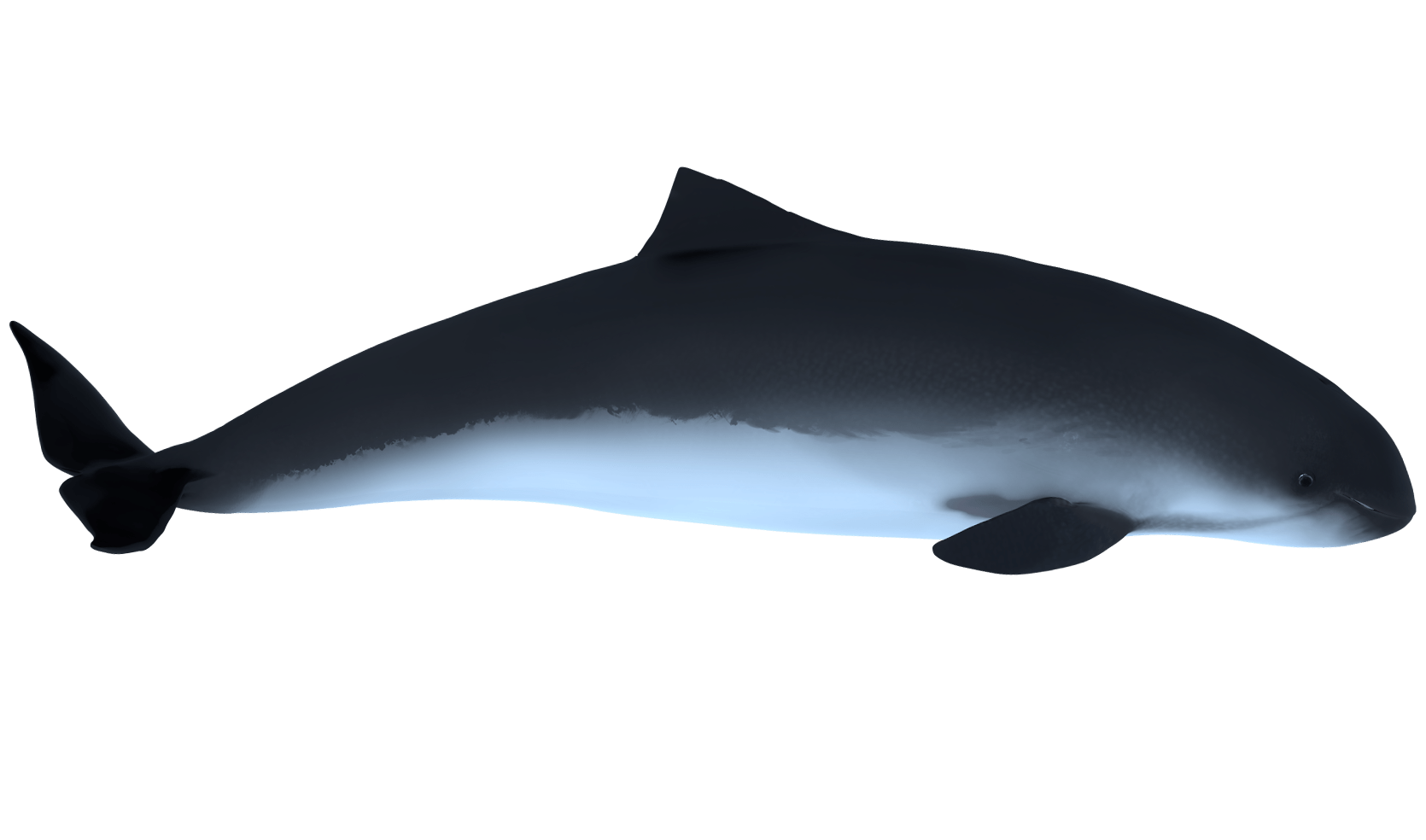

Harbour porpoise

Credits: GREMM

Dolphin

Credits: GREMM

Harbour porpoise

Credits: GREMM

Dolphin

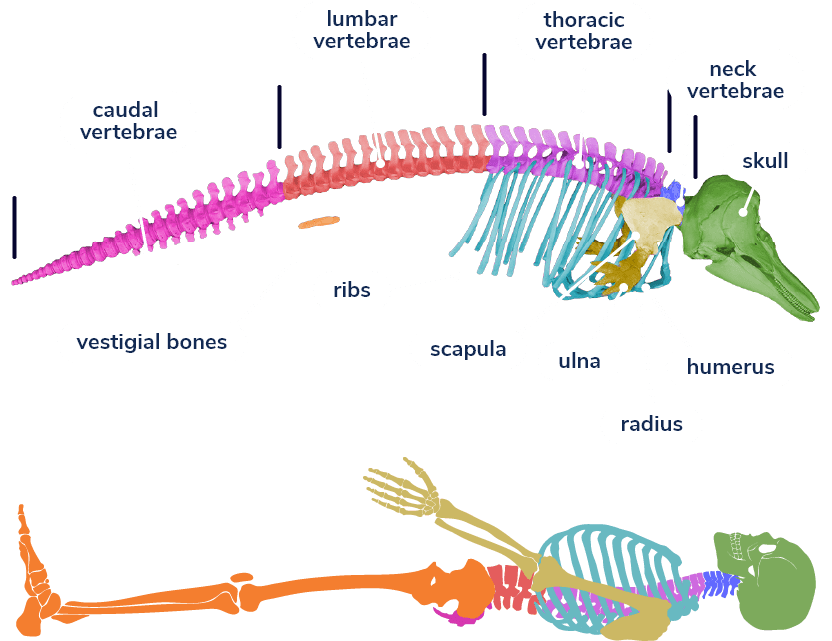

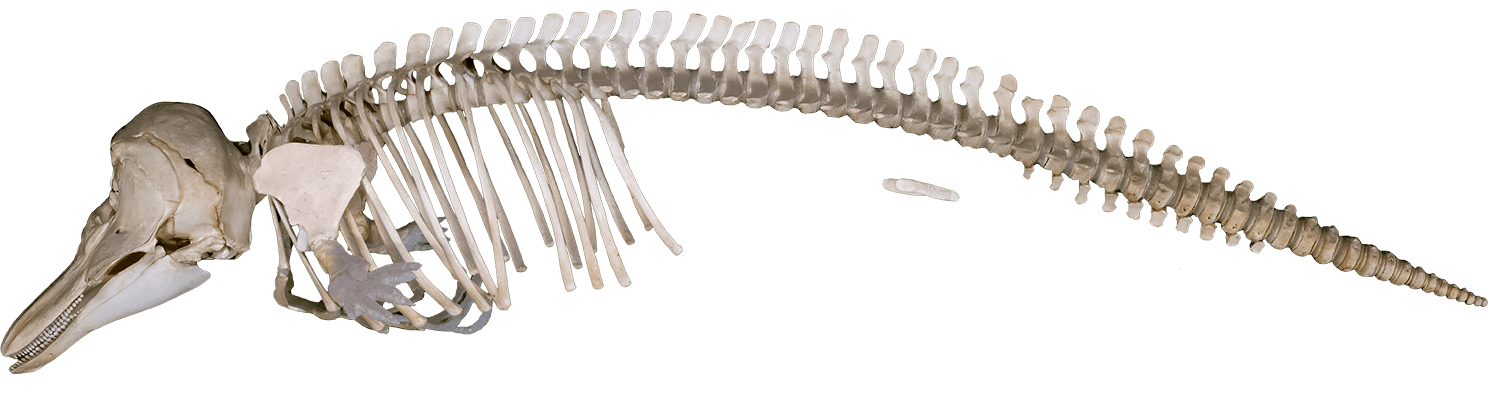

Whales have fingers! However, it is only by looking at a skeleton like Laurent’s that one can see them. In fact, the pectoral fins of cetaceans are made up of the same bones as our arms, but unlike humans, they have just a single joint at the shoulder.

They also have remnants of hind legs: a pair of small bones called vestigial bones that are detached from the remainder of the skeleton. As in most whales, the cervical vertebrae of porpoises are fused together and do not allow for neck movement. In humans, the caudal vertebrae are fused to form the sacrum and coccyx.

Who were whales’ ancestors?

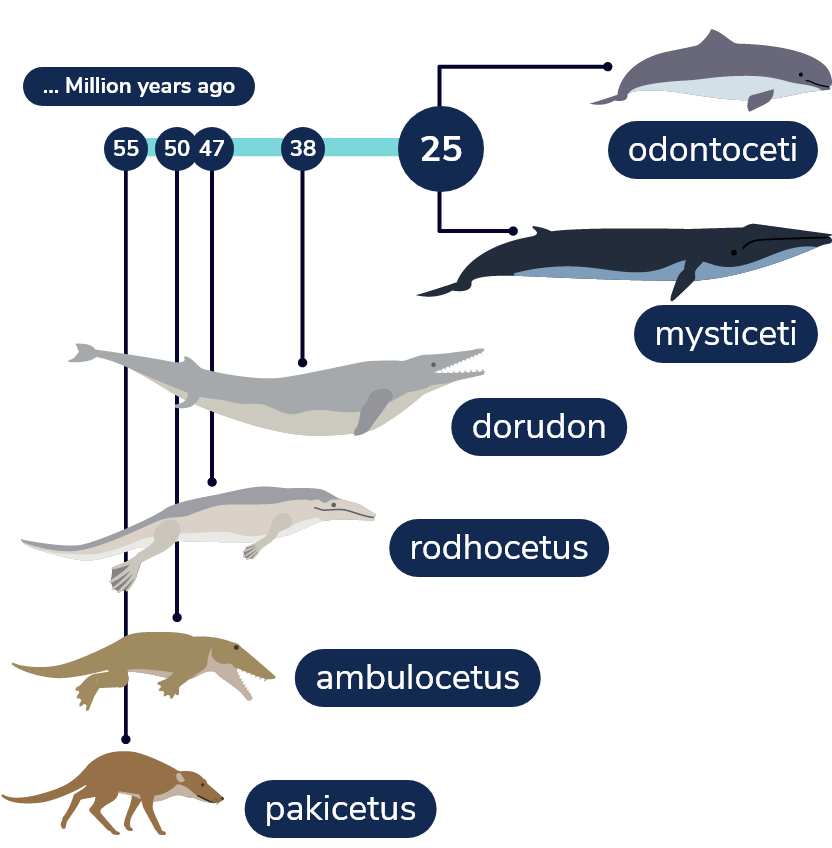

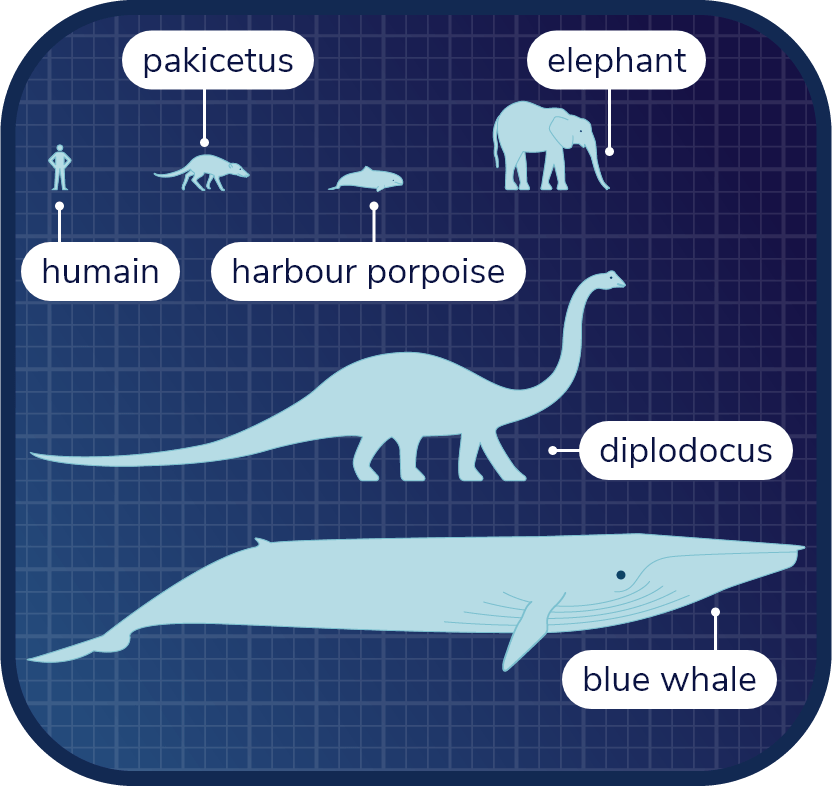

The animal considered to be the first cetacean is Pakicetus. And it walked on all fours! Measuring between 1 and 2 m long, this carnivorous mammal ventured into the water to find its food.

Pakicetus lived some 48 million years ago, after the dinosaurs had already become extinct. Today, the closest land relative of whales is the hippopotamus! To understand the evolution of animals, one mustn’t rely on appearances alone.

Pakicetus

How did whales go from a four-legged mammal to their present form?

It can be hard to imagine that an animal like Pakicetus could be the ancestor of whales. But one must not forget that this evolution occurred over the span of millions of years.

Thanks to the fossil record, researchers can trace the different stages of transformation undergone by cetaceans.

Pakicetus was a semi-aquatic animal with a thick bony wall around the inner ear. In Ambulocetus, a powerful tail evolved for propulsion and the feet were webbed. Later, in Rodhocetus, the nostrils migrated to the top of the head. Then it was the hind legs that got smaller and smaller. Those of Dorudon were tiny and were no longer even used by this animal, which had become completely aquatic. This species relied entirely on its caudal fin to propel itself through the water.

The morphologies of the whales that we are familiar with today appeared some 25 million years ago. They are divided into two main groups: odontocetes like Lawrence the porpoise, and mysticetes such as minke whales.

Over the course of millions of years, cetacean ancestors acquired various characteristics that ultimately led to the whales we know today.

Whale or cetacean: What’s the difference?

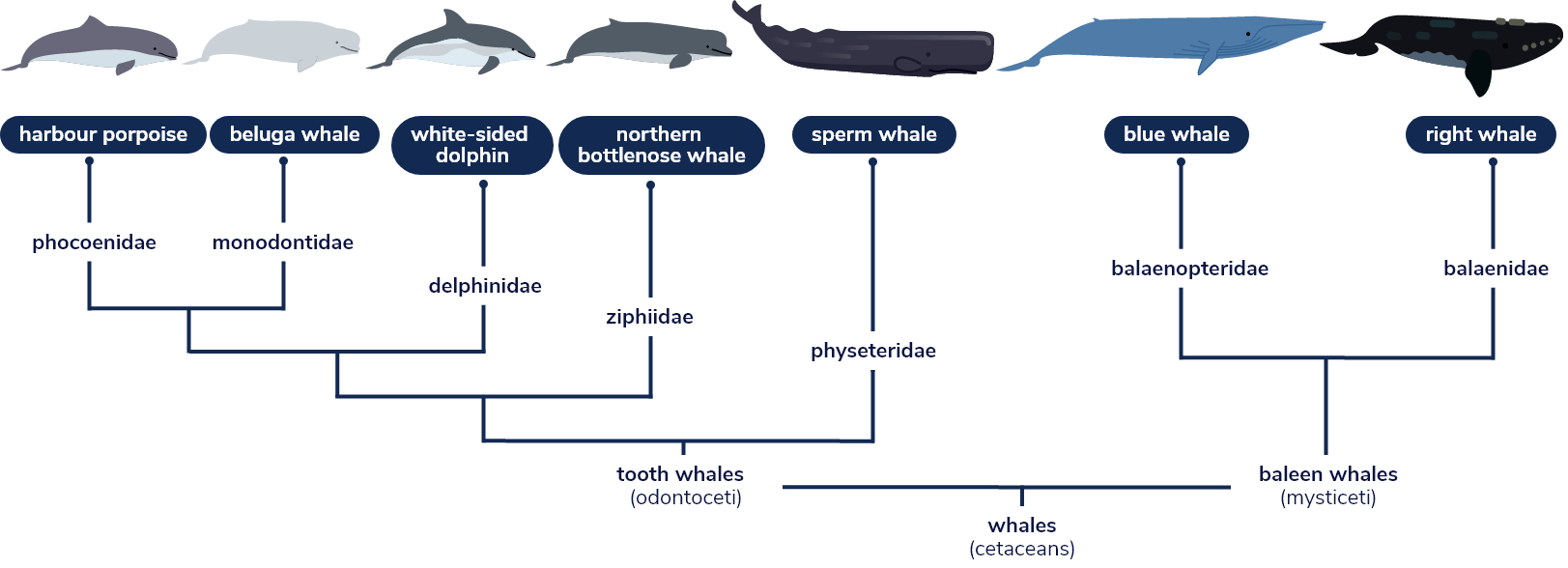

In the St. Lawrence, the term “whale” is often used interchangeably with “cetacean”. Porpoises, dolphins and rorquals are all whales but belong to different families. Rorquals (family Balaenopteridae) are baleen whales (mysticetes), whereas dolphins (family Delphinidae) and porpoises (family Phocoenidae) are toothed whales (odontocetes).

Phylogenetic tree of cetaceans illustrating all families present in the St. Lawrence.

A porpoise like Laurent may be similar in size to its land-roaming ancestors, but how do we explain the giant size of today’s blue whale and other mysticetes?

A porpoise like Laurent may be similar in size to its land-roaming ancestors, but how do we explain the giant size of today’s blue whale and other mysticetes?

In fact, the first mysticetes were not all that big, but a cooling of the Earth’s climate some 4.5 million years ago is believed to have led to ever larger animals.

In a colder climate, ice caps form in winter and melt in summer, releasing nutrients that accumulate in specific areas. These areas become very rich in plankton, but are often separated from other such areas by thousands of kilometres. For plankton-feeding whales, larger individuals are at an advantage because they are able to travel greater distances without overly depleting their reserves. Natural selection has therefore favoured large whales.

Whales spend over 90% of their time under water, where they go undetected by human observers. Studying them therefore presents an additional challenge. It is difficult to quantify a population or properly characterize its distribution.

In the Gulf of St. Lawrence, aerial surveys were carried out to estimate the number of porpoises in 1995 and 1996, but no estimates were made in Estuary waters.

Credits: Renaud Pintiaux

Whales are present by the thousands in the St. Lawrence, but it often happens that you stare at its surface and see absolutely nothing.

Considering the other threats faced by the species such as by-catch in fishing nets, the population status of the harbour porpoise in eastern Canada is classified as “Special Concern”.

However, it is much more difficult to implement adequate and effective protection measures when information is lacking.

Credits: GREMM

Drifting porpoise carcass in the St. Lawrence

What can be done to fill current knowledge gaps?

Invest more in scientific research.

To learn more about cetaceans like porpoises, we need to step up our efforts and invest additional human and financial resources.

Credits: GREMM

Research vessel operated by the Group for Research and Education on Marine Mammals (GREMM).

What can be done to fill current knowledge gaps?

Promote knowledge sharing

It is not enough to simply acquire knowledge; rather, we must be able to disseminate and share this knowledge if we wish to positively influence decisions pertaining to cetacean conservation.

Credits: Julia Zhogina

It is important to share scientific findings and opinions with concerned stakeholders. Here, Marie-Ève Muller, GREMM’s head of communications and spokesperson for the Quebec Marine Mammal Emergency Response Network, gives a scientific presentation on the coexistence of cruises and whales at a conference attended by a number of international cruise lines.

Who were whales’ ancestors?

The animal considered to be the first cetacean is Pakicetus. And it walked on all fours! Measuring between 1 and 2 m long, this carnivorous mammal ventured into the water to find its food.

Research projects that receive funding are those that address questions of public interest. So, the more people there are who take an interest in the fate of cetaceans, even more discreet species such as harbour porpoises, the greater the likelihood that more projects will take shape to fill these knowledge gaps.

A GREMM naturalist gives an explanation about whales.

Now that you’ve heard Laurent’s story, let’s go meet the other whales!

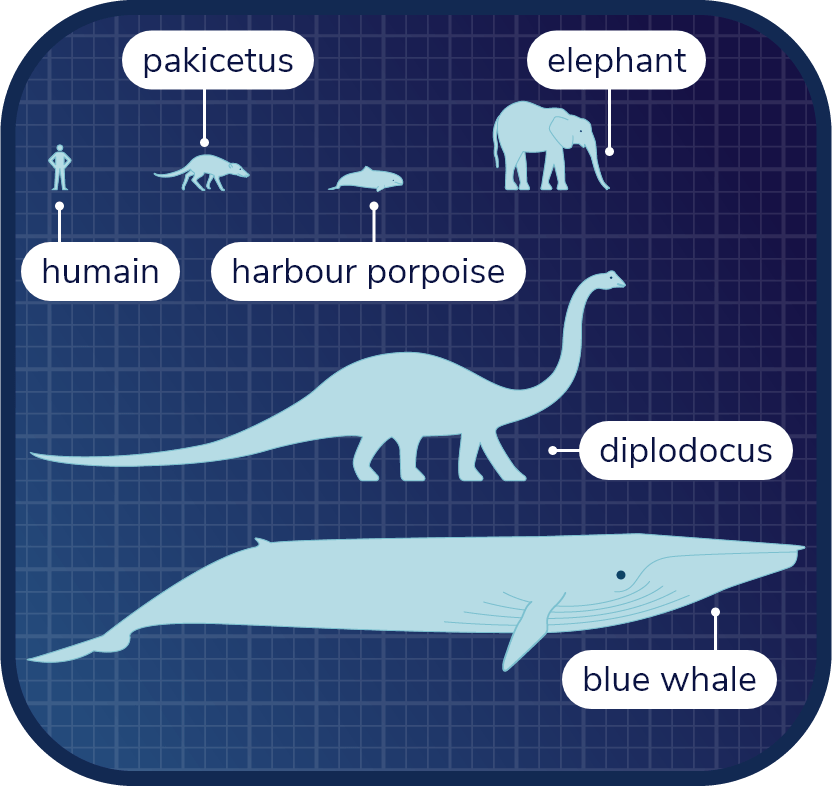

Harbour porpoise

Phocoena phocoena

Characteristics

Harbour porpoises of eastern Canada

Weight

45 to 50 kg, up to 70 kg

Length

1.3 to 2 m

Lifespan

20 years

Population

approx. 21,000 individuals

Status

Special concern

Laurent

Weight

unknown

Length

unknown (skeleton: 1.05 m)

Birth - Death

unknown - late 1980s

ID number

not known to researchers

Sex

unknown

The small skeleton belonging to Laurent was one of the first occupants of the Marine Mammal Interpretation Centre.

Harbour porpoise

Phocoena phocoena

Characteristics

Harbour porpoises of eastern Canada

Weight

45 to 50 kg, up to 70 kg

Length

1.3 to 2 m

Lifespan

20 years

Population

approx. 21,000 individuals

Status

Special concern

Laurent

Weight

unknown

Length

unknown (skeleton: 1.05 m)

Birth - Death

unknown - late 1980s

ID number

not known to researchers

Sex

unknown

The small skeleton belonging to Laurent was one of the first occupants of the Marine Mammal Interpretation Centre.