Known for their “chattiness”, belugas lead active social lives.

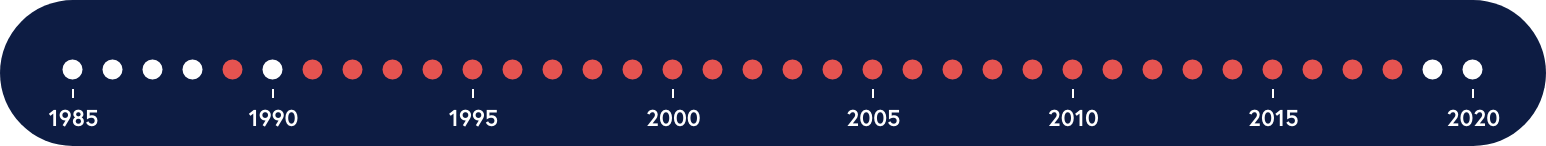

Researchers from the Group for Research and Education on Marine Mammals (GREMM) first photographed Athena in 1989.

Amongst other field marks, she can be recognized by the deep scar with jagged contours on her right side. Ever since this first encounter, she has been seen every year except for 1990.

Credits: GREMM

Athena’s back (right flank) photographed in 2018.

Years in which Athena was observed.

On July 29, 2018, a beluga carcass is spotted by two individuals in the Saguenay Fjord. They contact Marine Mammal Emergencies. Thanks to their photos, researchers are able to recognize Athena !

And yet, she had been photographed alive and well just two days earlier! She is transported to the Université de Montreal’s Faculty of Veterinary Medicine for a necropsy (an autopsy performed on an animal). Despite the analysis, scientists were unable to pinpoint the cause of Athena’s death. Athena died at the age of 45.

Credits: Raymond Cardin

Athena's carcass drifting in the Saguenay Fjord. It is realized that this is not a beluga at rest but rather a carcass, as the animal is turned on its side and its pectoral fin is visible.

Credits: GREMM

The carcass of DL0030, a.k.a. Athena, is removed from the water and transported to the Université de Montréal's Faculty of Veterinary Medicine.

Credits: GREMM

Stéphane Lair and his team from the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine at Université de Montréal perform a necropsy to try to pinpoint the cause(s) of mortality. (Not Athena in this photo, but an adult male beluga)

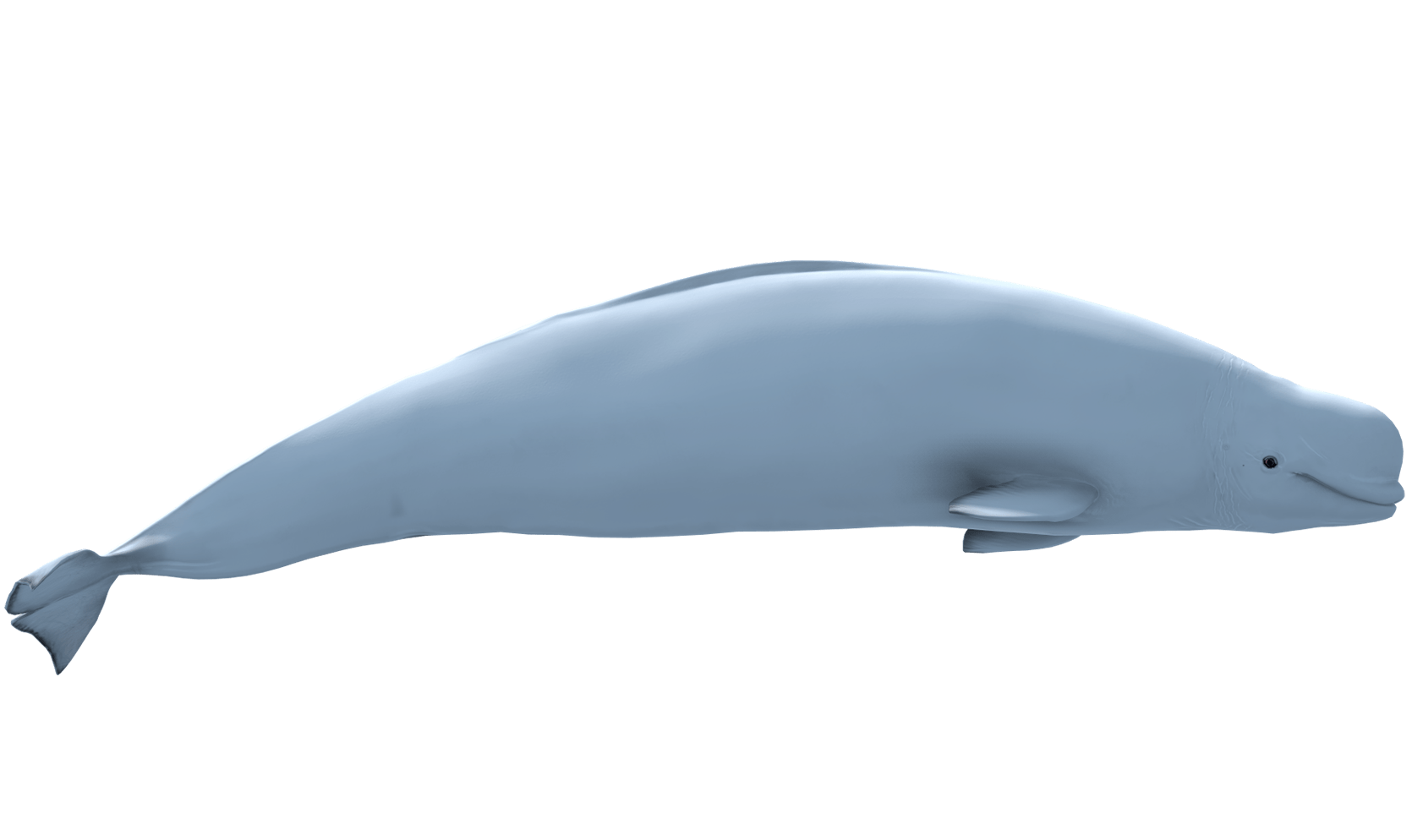

When Athena was encountered for the first time, she was at least 14 years old. How do we know? Because she was already all white.

Belugas change in colour as they age! Café au lait in colour at birth, they later turn bluish-grey and then all grey around the age of 3. Later they grow paler, turning really white between the ages of 14 and 16.

Credits: GREMM

These three belugas can be ranked from oldest to youngest by their colour, with the darkest being the youngest and the lightest, the oldest.

Credits: GREMM

Adult female and her first-year calf.

Credits: GREMM

Adult female with a one- or two-year-old calf, which French speakers sometimes refer to as a bleuvet due to its bluish-grey colour.

Athena belonged to the beluga community that frequents the Saguenay Fjord. Research has shown that belugas use the same territory every summer.

Males and females generally stay in separate groups. They also associate with certain individuals more frequently than others. Athena's swimming companions were Slash, Blanche, Blanchon, Griffon and Élizabeth.

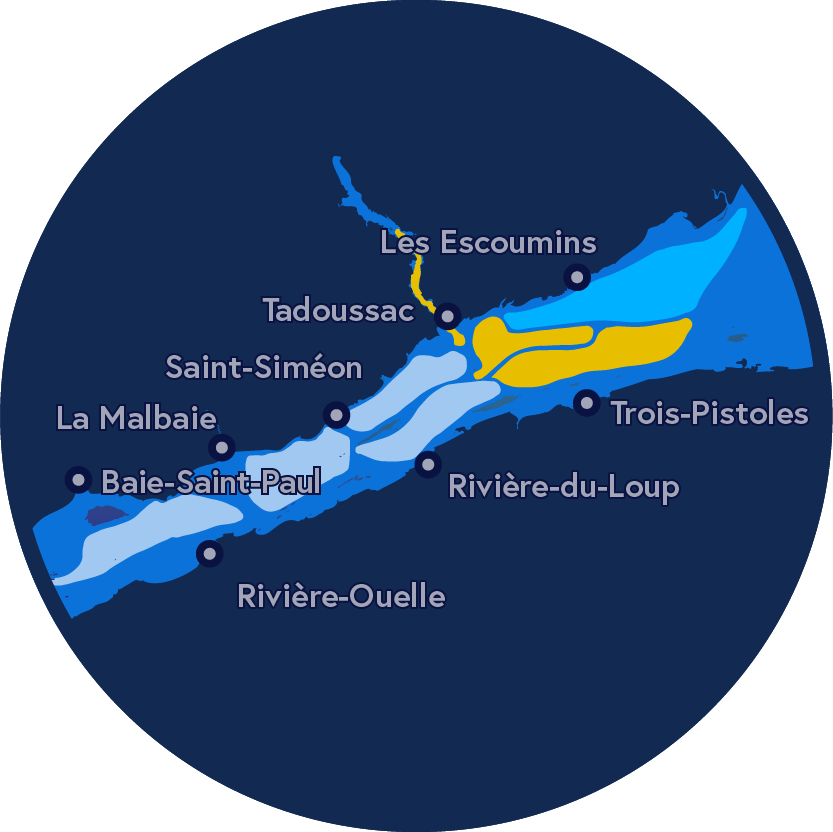

In summer, the St. Lawrence beluga’s distribution is centred around Tadoussac. The population is divided into three main sectors: the upstream sector, the central sector and the downstream sector.

To keep in touch with her companions or relocate them after a separation, Athena probably used what is called a “contact call”.

Our collaborator Valeria Vergara of Ocean Wise has discovered that this is the first call belugas learn as calves, but they must practise so that it becomes as loud and clear as that of the adults.

Credits: Valeria Vergara, Ocean Wise

The images and sounds were captured in Baie Sainte-Marguerite (a bay in the Saguenay) using a drone and a hydrophone. We can hear the belugas making contact calls, which sound like creaking doors.

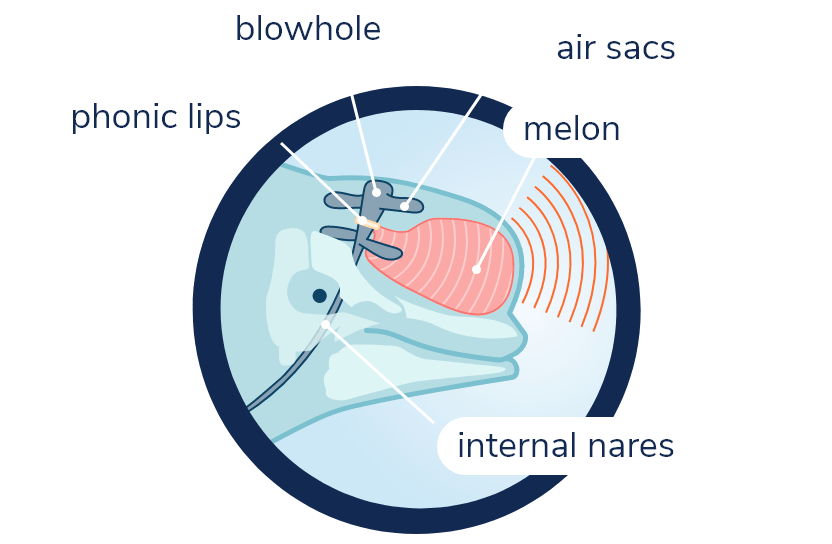

How do Athena and other toothed whales produce sounds ?

Sounds are not produced by vocal cords in the larynx like in humans, but by similar structures found inside the blowhole. Whales therefore do not need to open their mouths to communicate, as sound is transmitted directly through the melon.

1. First, air passes through the nasal passages, vibrates the phonic lips and produces sound. It’s almost like these whales are talking through their nose!

2. Then the sound waves pass through the melon before being emitted into the environment. The melon acts as an acoustic lens. In other words, the melon will adjust the sounds a little like a lens adjusts images.

3. Lastly, how do whales produce sounds while holding their breath? Try it for yourself... you’ll see that it does not work very well. Thanks to their vestibular sacs, whales can store and reuse air to produce sounds.

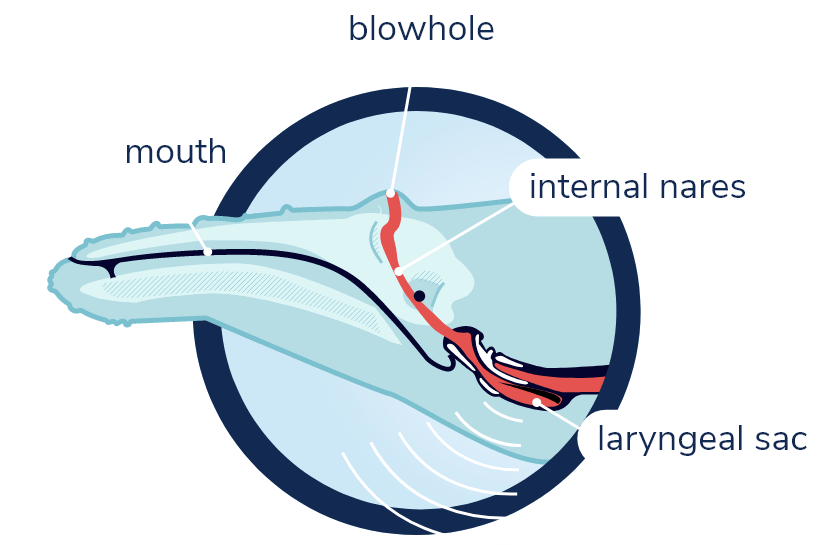

How do baleen whales produce sounds ?

Baleen whales do not have phonic lips or melons. Rather, it is believed that their sounds are produced in the throat, a bit like humans with our vocal cords.

But to avoid letting the air escape, they also have an organ in their larynx called the laryngeal sac. This allows them to recycle the air and make a new sound without having to take another breath.

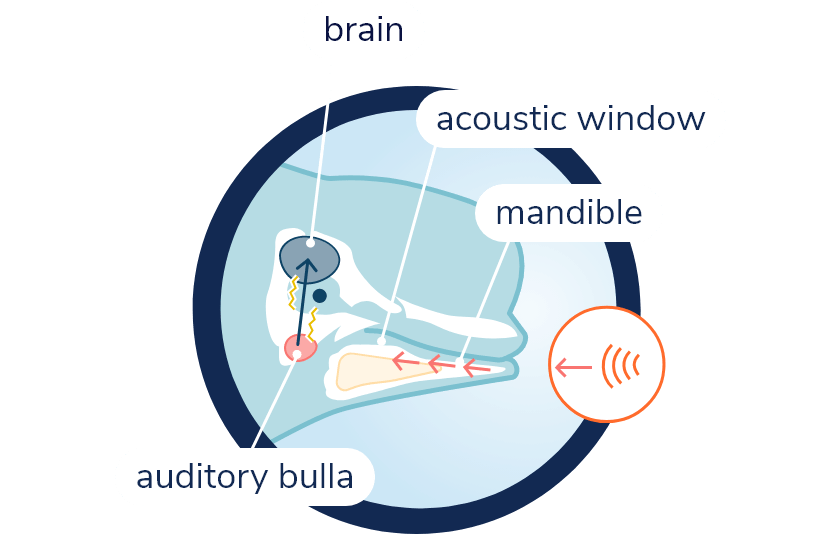

How do whales hear ?

Sounds are received by the jaw and transmitted to the tympanic bulla. This causes the ossicles to vibrate, which causes the cochlea to vibrate, which then sends the signal to the brain.

1. It is believed that sounds are first received by the jaw. Unlike humans, whales do not have external ears. The jawbone of whales is hollow and contains fatty tissue called the acoustic window.

2. Sounds then travel through the acoustic window to the tympanic bulla (the bone that protects the middle ear). In whales, this is found outside the skull and has a very thick wall.

3. Next, the sound vibrates the tympanic bulla, which vibrates the small bones inside, which in turn vibrate the cochlea (the tiny spiral-shaped organ of the inner ear). The cochlea then sends the signal to the brain.

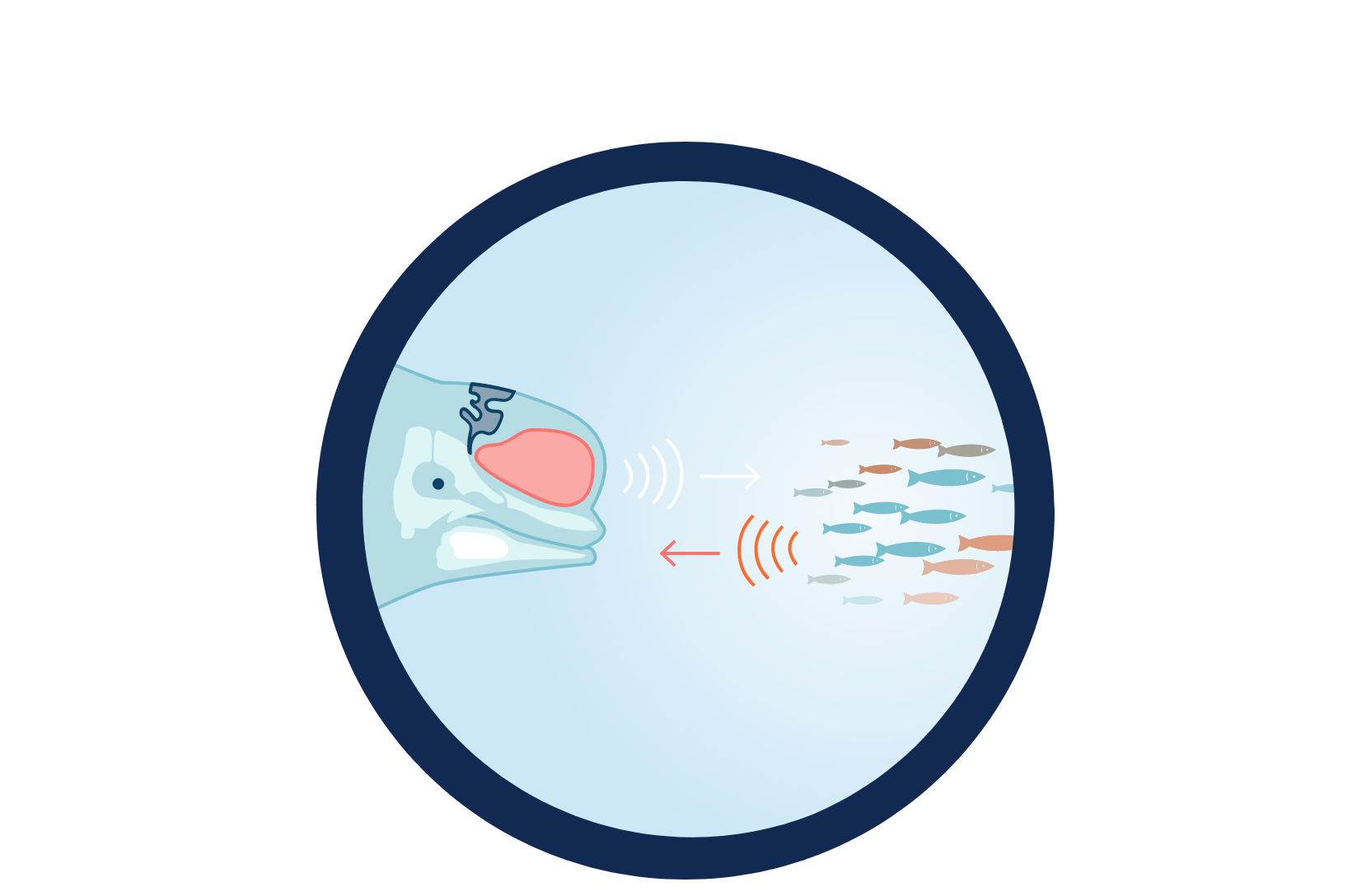

How does echolocation work ?

Echolocation allows toothed whales to know not only how far away an object is, but also how dense it is. It works like a natural sonar. The whale produces ultra-high frequency clicks and then picks up their echoes.

Try it for yourself !

Give a little tap to a piece of metal, wood or glass. Does it make the same sound ? No, it does not. Likewise, the echo returning to the whale will vary depending on the density of the object or the prey in question.

How can we mitigate noise pollution ?

Simply slowing down can help make a watercraft quieter.

In the Saguenay-St. Lawrence Marine Park, amongst other noise-reduction measures in beluga habitat, merchant ships are requested to voluntarily reduce their speed to 10 knots. According to collected data, the majority of vessels are currently complying with this request.

Credits: GREMM

The engine turns the propellers, which drive the boat. The more the boat accelerates, the faster its engine and therefore its propellers turn. This usually produces more noise as well.

How can we mitigate noise pollution ?

By protecting areas from boat traffic or other noisy activities, quieter areas known as acoustic refuges are created.

This is the case with Baie Sainte-Marguerite in the Saguenay Fjord. Since 2018, this gathering place for belugas from Athena’s community has been closed to boating during the summer months.

Credits: GREMM

Baie Saint-Marguerite is a gathering place for many St. Lawrence belugas.

What can we do to help mitigate noise pollution ?

Pleasure craft are a common sight on the St. Lawrence and Saguenay. It is therefore possible to do your part by paying attention to your own behaviour when you’re out on the water.

For example, by reducing your speed and keeping your distance from belugas and other marine mammals, you can help improve their acoustic environment.

Credits: GREMM

Many boaters navigate through whale habitat, and they all have a role to play to ensure a peaceful coexistence with marine mammals and other wildlife.

Now that you’ve heard Athena's story, let’s go meet the other whales!

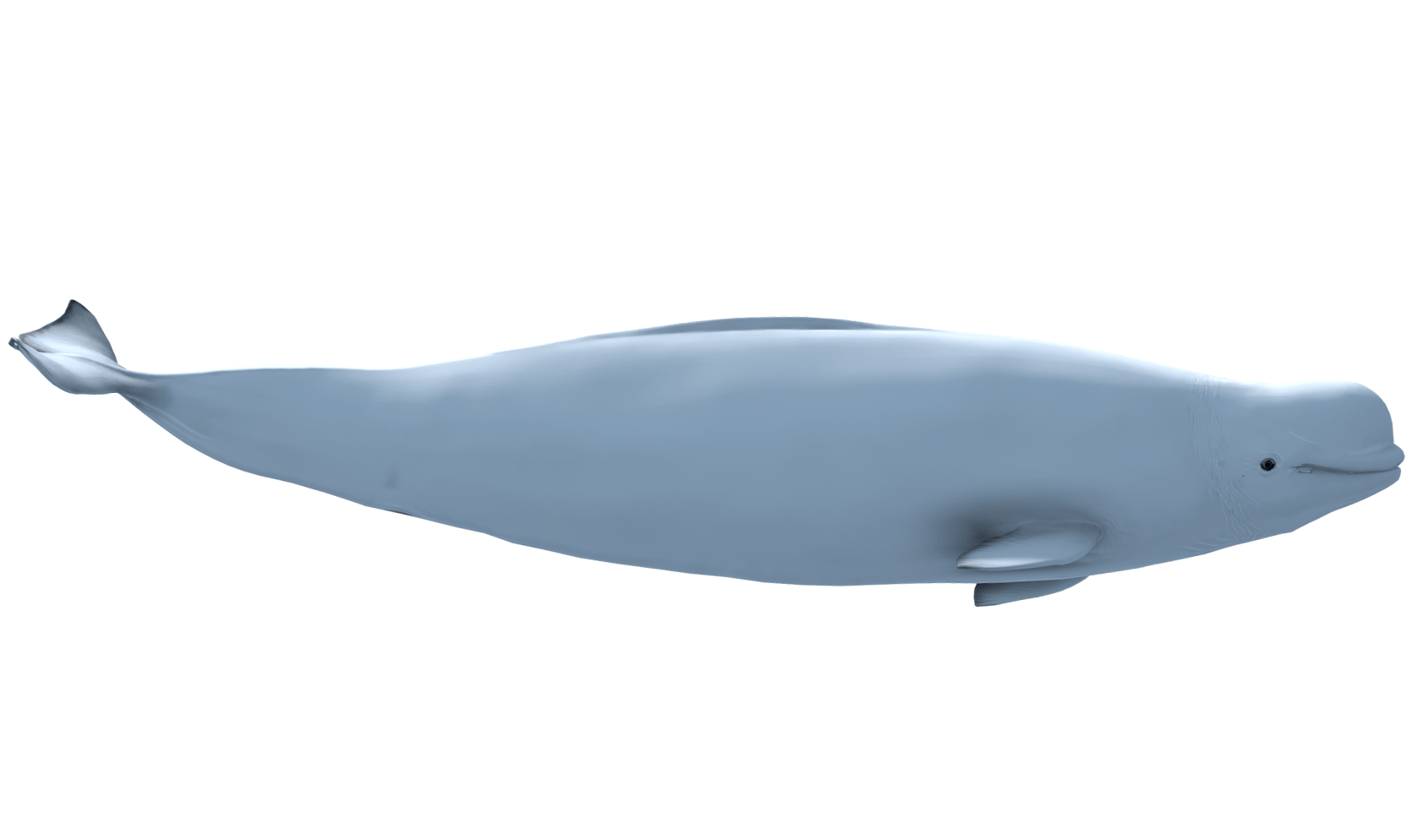

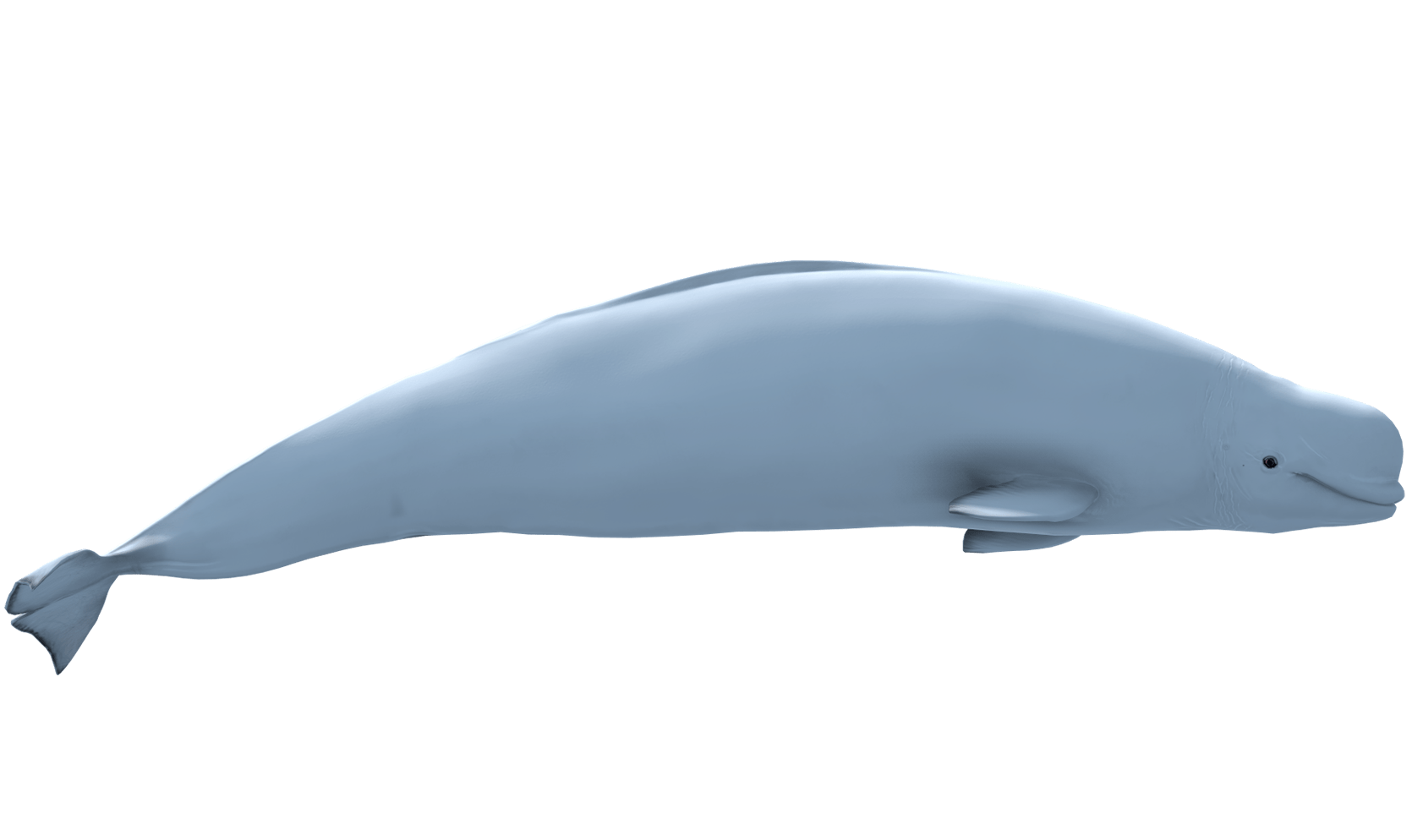

Beluga whale

Delphinapterus leucas

Characteristics

Belugas of the St. Lawrence

Weight

700 to 1500 kg up to 2000 kg

Length

2.5 to 4.5 m up to 5 m

Lifespan

60 years

Population

900-1000 individuals

Status

Endangered

Athena

Weight

633 kg

Length

3.63 m

Birth - Death

1973 - July 2018

ID number

DL0030

Sex

Female

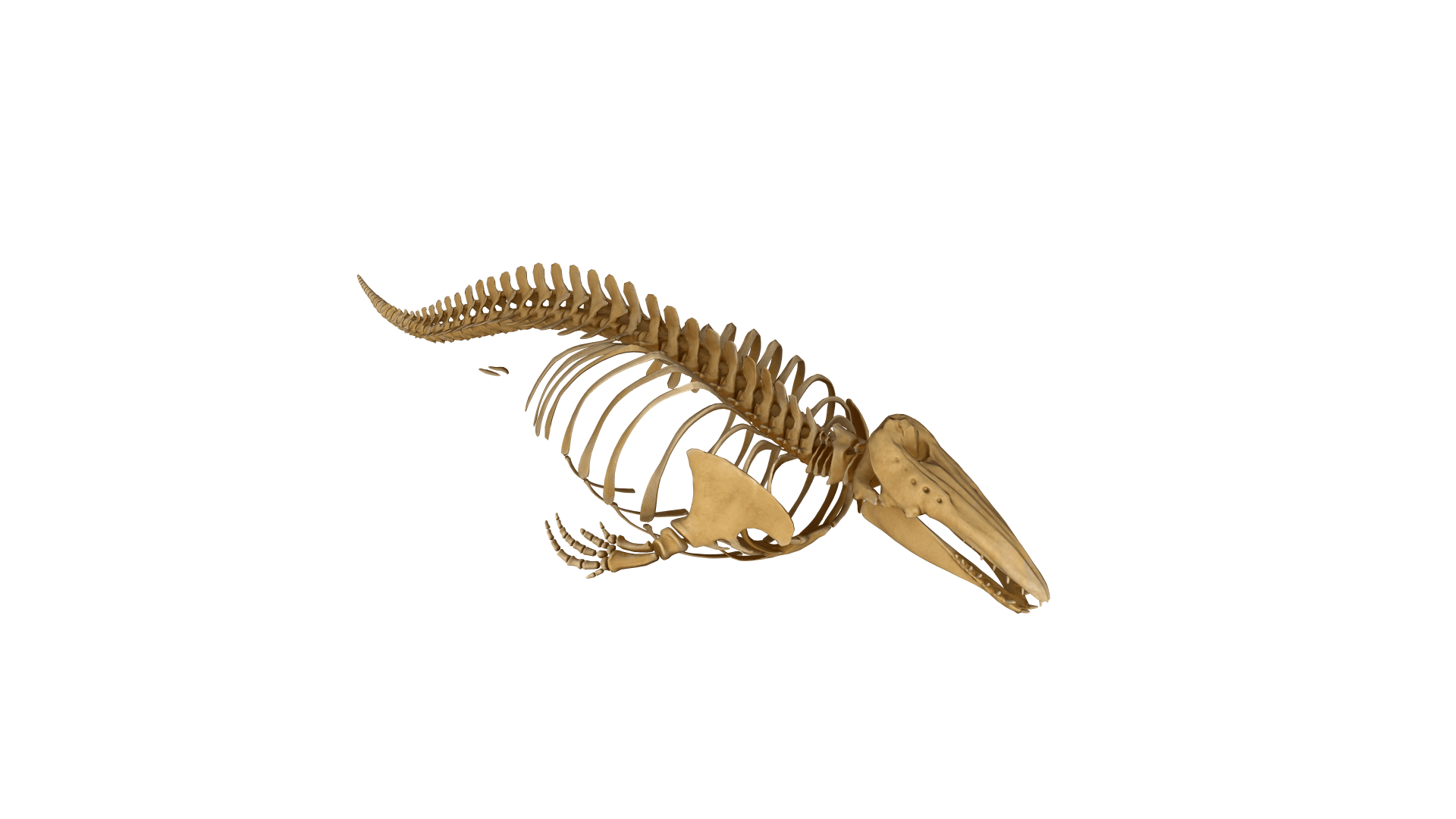

Photo of a real beluga skeleton. However, it is not Athena, as her skeleton was never preserved. Very little is known about this individual, who was recovered in the St. Lawrence in the 1980s. But who knows, Athena may have already swam with this beluga!

Beluga whale

Delphinapterus leucas

Characteristics

Belugas of the St. Lawrence

Weight

700 to 1500 kg up to 2000 kg

Length

2.5 to 4.5 m up to 5 m

Lifespan

60 years

Population

900-1000 individuals

Status

Endangered

Athena

Weight

633 kg

Length

3.63 m

Birth - Death

1973 - July 2018

ID number

DL0030

Sex

Female

Photo of a real beluga skeleton. However, it is not Athena, as her skeleton was never preserved. Very little is known about this individual, who was recovered in the St. Lawrence in the 1980s. But who knows, Athena may have already swam with this beluga!