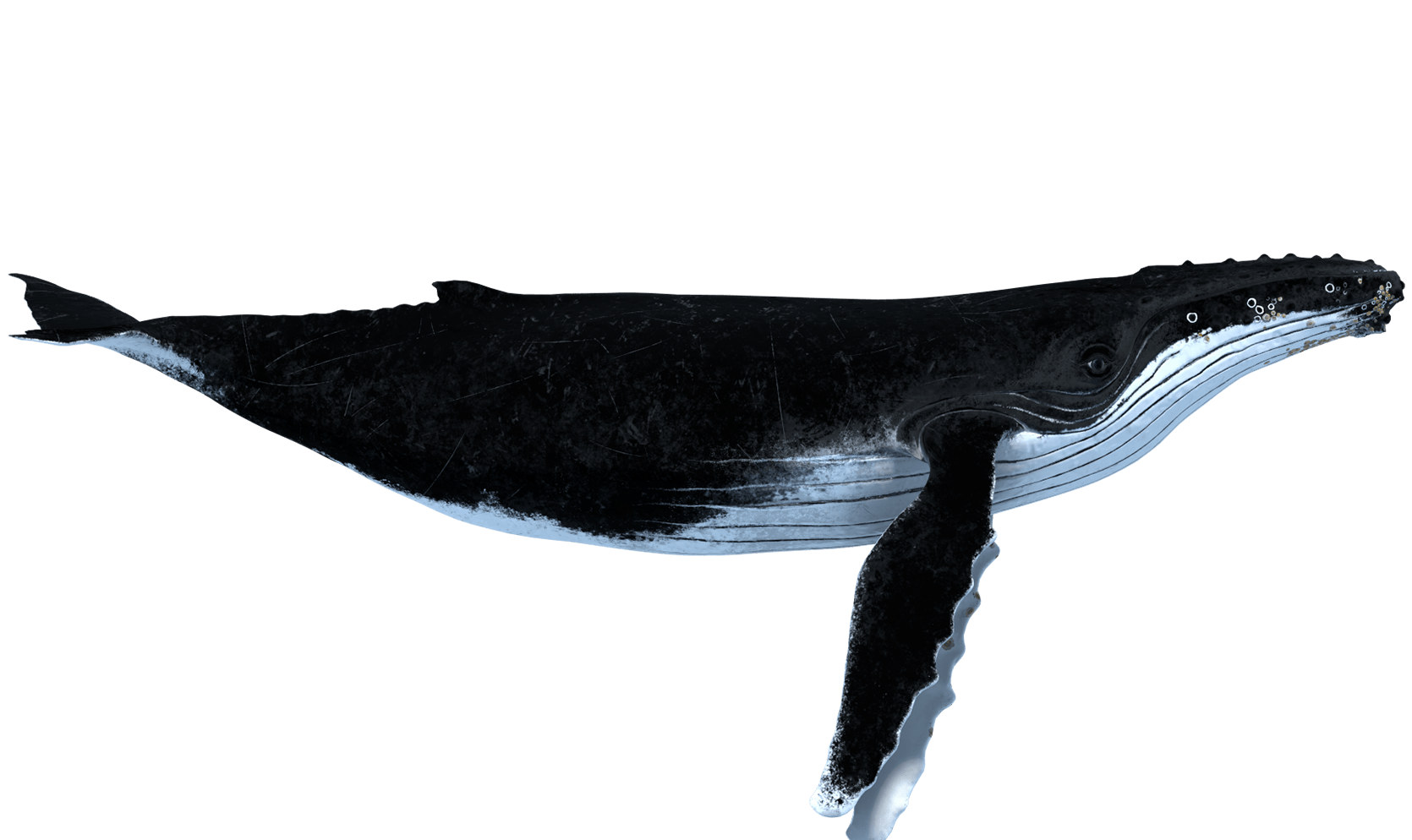

Humpback whales like Godbout often impress us with their exuberant behaviours, including full breaches and fin slapping.

Having never been photographed prior to the discovery of her carcass, Godbout was unknown to researchers. To identify individual humpbacks, scientists mainly rely on the colour pattern of the underside of the tail, which the whales reveal when they dive.

These patterns are often quite distinct and sometimes allow observers to recognize a well known individual at a single glance.

Credits: GREMM

Tic Tac Toe is a very famous female in the St. Lawrence. She has been observed in these waters every year since 1999.

Credits: GREMM

H858 is a young humpback whale that has been known in the St. Lawrence since 2017.

On May 3, 2017, the carcass of a young female humpback whale washes ashore in the village of Godbout in Quebec’s Côte-Nord region. In an attempt to discover the cause of death, a necropsy is performed.

Necropsies are not conducted systematically, especially when the animal’s population is doing well, as is the case with humpbacks. However, at the time when Godbout was found, high mortality rates were being observed for humpbacks in the United States, which prompted researchers to investigate.

Credits: Cyndi Gauthier

Godbout’s carcass is found on May 3, 2017 on the beach of the village that eventually earned this whale her name. A volunteer from the Quebec Marine Mammal Emergency Response Network is dispatched to document the situation and secure the carcass. The following evening, May 4, the carcass is moved to higher ground to ensure it is beyond the high tide line.

Credits: GREMM

On the morning of May 5, Godbout’s carcass is loaded onto a trailer and transported to the Ragueneau landfill, where it will be flensed and inspected to determine the possible causes of her death.

Credits: GREMM

During a necropsy, all of the animal’s organs are inspected. Upon opening the digestive tract, the flensing team found it to be almost completely empty, except for a small amount of digested food near the end of the tract. The whale also appeared emaciated, suggesting that it may have been undernourished. However, it is difficult to pinpoint the exact cause of death.

Credits: GREMM

Once the flensing was complete, Godbout’s bones were placed in a container for the next stage of cleaning. While the bones macerated in this container, part of the job was done by maggots!

Godbout had large barnacles still attached to her skin, which suggests that she had arrived in the St. Lawrence only recently. These crustaceans attach themselves to the skin of humpbacks during their winter stays in the warm waters of the Caribbean.

However, they fall off once they are exposed to cold water. Other barnacles latch onto the humpbacks in the cold St. Lawrence, but these species are smaller. These crustaceans feed by filtering water and are rarely bothersome to the whale.

Credits: GREMM

This is what the barnacles looked like on Godbout’s skin. The $2 coin isn’t there by accident; it was purposely placed there to give the viewer an idea of how big the barnacles are.

Credits: GREMM

On the tips of the tail of this humpback diving into the St. Lawrence are small, round, beige-coloured shells: these are barnacles attached to the animal’s skin.

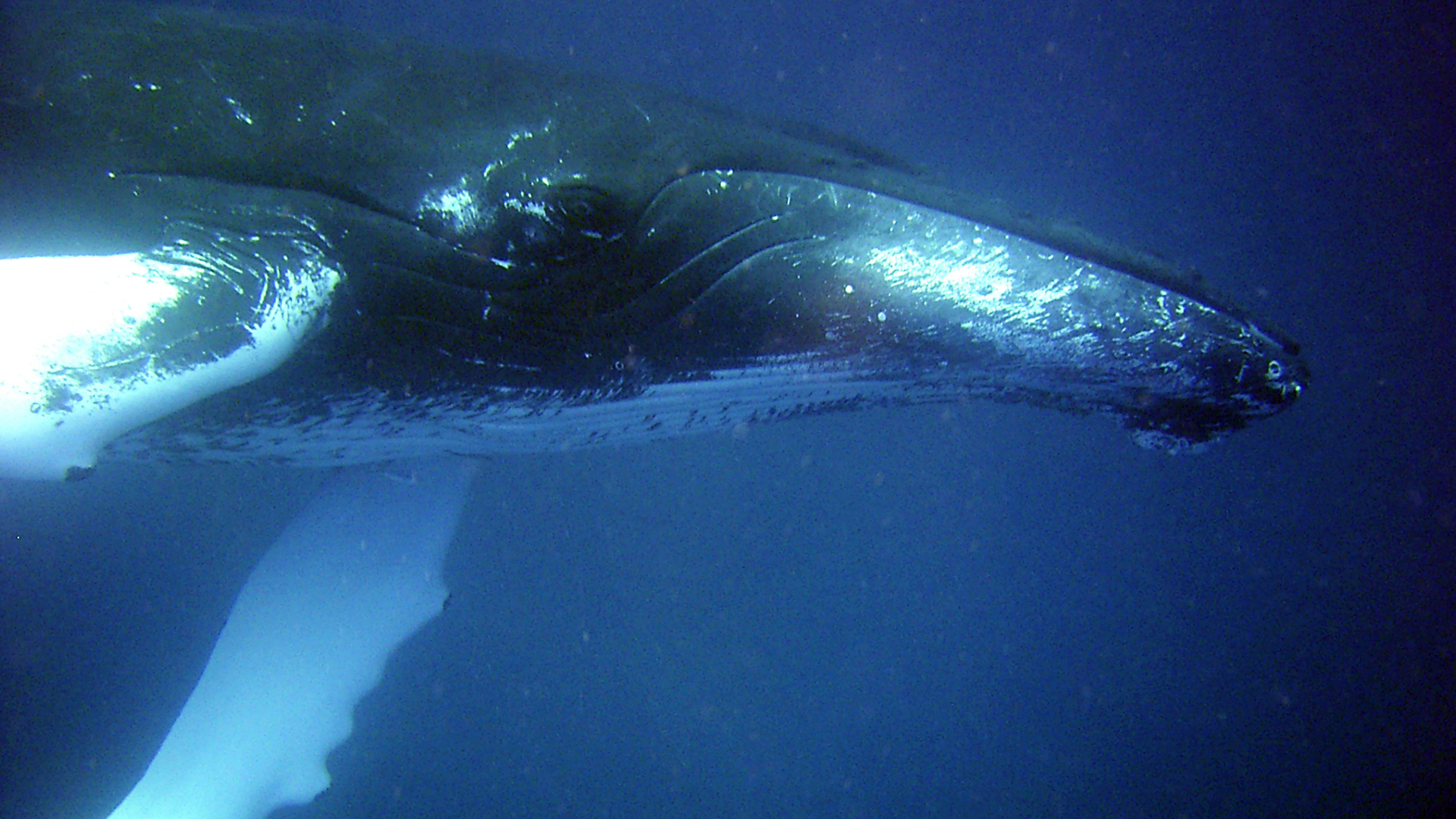

In winter, when humpbacks congregate in temperate waters for the breeding season, the males all sing the same refrain. But they don’t just perform, they also compose...

In fact, they create a new “hit” every season! Over the weeks, they gradually tweak their tune. The following year, they pick up where they left off, singing last season’s melody and then modifying it once again.

Credits: NOAA

It is especially in the clear waters of the tropics that males sing their serenades.

The largest appendages in the entire animal kingdom, the pectoral fins of humpbacks are particularly impressive. Amongst other things, they are believed to help the animal regulate its body temperature.

For Godbout and her species, which migrate back and forth between temperate and cold waters, proper temperature regulation is a critical matter. These large fins also allow them to perform a wide variety of underwater manoeuvres such as spinning or tumbling. Humpback whales have even been seen using their fins to corral fish in front of their mouths.

Credits: GREMM

The fins’ jagged edges are clearly visible. This particular morphology is believed to reduce friction in the water. Engineers have even drawn inspiration from humpback whale fins for the design of turbines, propellers, aircraft wings, etc.

In water, the body loses heat much more easily than in the air. To limit such heat losses, whales have a thick layer of blubber.

On land, some animals have heavy fur coats to protect themselves from the cold. But even the warmest fur wouldn’t be very effective in water. It is actually the layer of air trapped between the hairs that provides insulation. Whales therefore have bare skin.

Credits: GREMM

Even if it was rather significant, Godbout’s blubber was found to be somewhat thin for her species.

Credits: GREMM

Slice of skin and blubber from the carcass of Piper the right whale. Right whales have particularly thick layers of blubber.

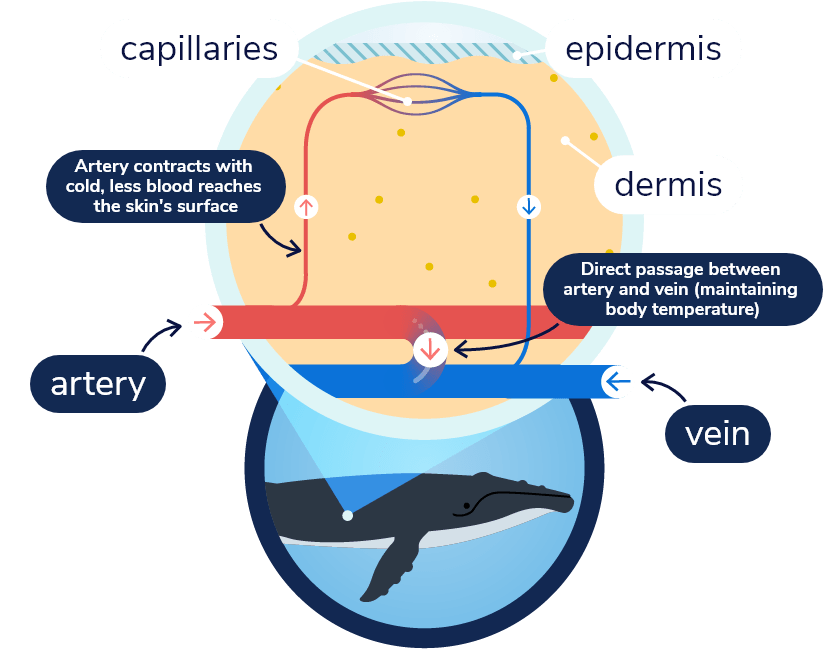

How do whales retain their heat?

When a whale needs to conserve heat, the arteries that run through its blubber layer constrict. Only a small volume of blood – just enough to keep the cells alive – can then reach the skin surface.

Most of the blood is re-channelled directly to the veins below the blubber. This way, blood returning to the body’s insides hardly loses any heat at the skin surface.

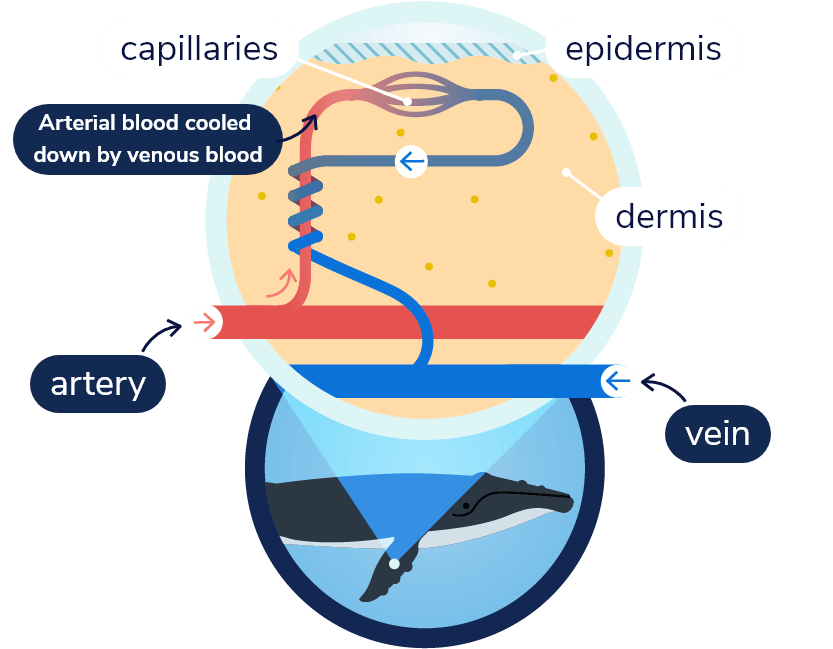

How is heat retained in the extremities, where there is very little blubber?

The circulatory system of whales has evolved into a perfect heat exchange system. The arteries that bring warm blood to the extremities are surrounded by a network of veins that carry blood back toward the body’s insides.

There is therefore an exchange of heat that takes place between the arteries and the veins. Instead of losing all of its heat at the skin’s surface, the warm blood from the arteries raises the temperature of the blood in the veins.

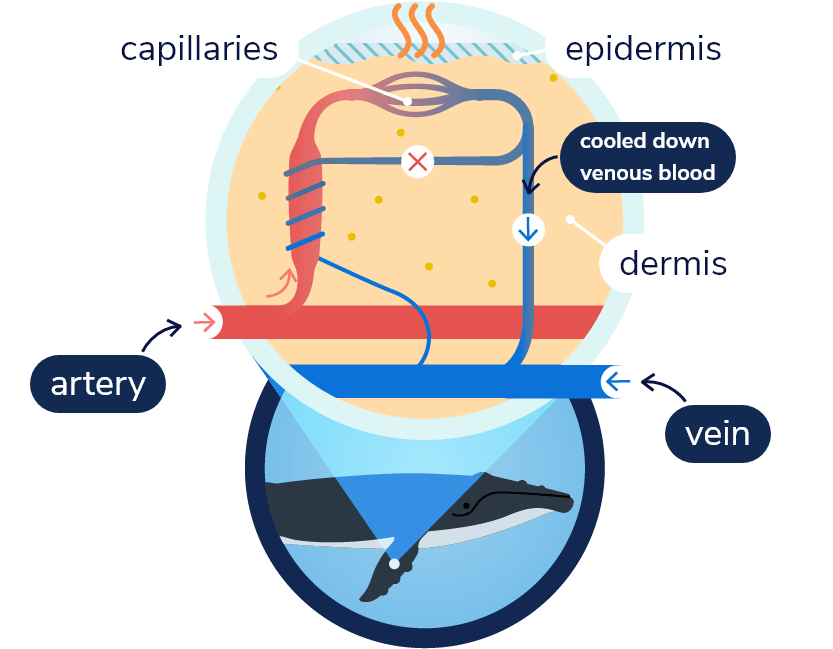

Can a whale ever get too hot?

Even in 4°C water, a whale can get hot if it is active. The animal therefore needs some way to release excess heat. Fortunately, there is a solution in the heat exchange system!

When a whale gets hot, its arteries dilate, crushing the network of veins around them. Blood that has cooled at the skin’s surface must then return by another route, so it returns directly to the general circulation without first being warmed by the arteries.

Are whales prone to hypothermia?

Humpback whales are generally quite well adapted to retain their body heat in cold water, but this is not the case for all species. A striped dolphin was once discovered in Tadoussac.

This species generally lives in more temperate waters of the Atlantic. Experts consider that the dolphin found stranded on the North Shore of Quebec died of hypothermia. It is believed to have followed a group of Atlantic white-sided dolphins from the ocean to the St. Lawrence Estuary. It is precisely in this region that the waters of the St. Lawrence are coldest. Since Godbout had a thinner layer of blubber, is it possible that she was cold?

Credits: GREMM

In October 1992, the carcass of a striped dolphin was found on the beach in Tadoussac.

Humans once hunted whales in great numbers in order to harvest this blubber. So much so that several populations of cetaceans, including humpbacks, have been decimated by whaling.

Commercial whaling was formerly practised in the St. Lawrence. Initially, whalers targeted mostly right whales, but as this species declined they increasingly turned to humpback, blue and fin whales. For years, whale oil was used to light up streets and homes.

Credits: BAnQ Sept-Îles, P6, S3, D4, P946 – photographer unknown – photo restored by Alain Dupuis

A whale oil refinery in the Bay of Sept-Îles, Quebec, circa 1910

Commercial whaling probably decimated 90-95% of the world’s humpback whale population. Today, humpbacks are no longer harvested.

In the mid-20th century, the International Whaling Commission was founded in an effort to regulate whaling, which would eventually be banned by many countries. However, even after whaling ended, humpback whale populations seemed to be slow to bounce back. Other issues such as entanglement in fishing gear complicated their recovery.

Credits: GREMM

Efforts have been made to help humpbacks. The population to which Godbout belonged is now growing. Since 2003, the new status of the population is “Not at Risk”.

Fewer humpback whales are getting themselves caught in fishing nets. At the same time, rescue teams have become more efficient at releasing entangled whales.

Credits: Renaud Pintiaux

Group of humpback whales in the St. Lawrence Estuary.

What can be done to help other species recover?

Carefully focus on the specific issues affecting the species in question.

Not all cetacean species and populations are impacted by various issues in the same way. Depending on their habits, some may be most affected by entanglements, while others may be particularly threatened by contamination, for example. A proper understanding of what threatens their survival can help facilitate more concrete actions to improve their fate.

What can be done to help other species recover?

Pay attention to past success stories.

It is important to focus on the threats faced by whales, but it is equally relevant to recognize what we have done right! A better understanding of the factors that have led to the recovery of one species can serve as an inspiration for helping other species. We must celebrate our victories to maintain hope and find the strength to tackle subsequent challenges.

Credits: GREMM

Left pectoral fin of a humpback whale.

Now that you’ve heard Godbout’s story, let’s go meet the other whales!

Humpback whale

Megaptera novaeangliae

Characteristics

Northwest Atlantic humpback whales

Weight

30 to 40 tons

Length

13 to 17 m

Lifespan

Environ 80 ans

Population

approx. 12,000 individuals

Status

Not at risk

Godbout

Weight

7.4 tons

Length

9.04 m

Birth - Death

probably 2016 - May 2017

ID number

not known to researchers

Sex

Female

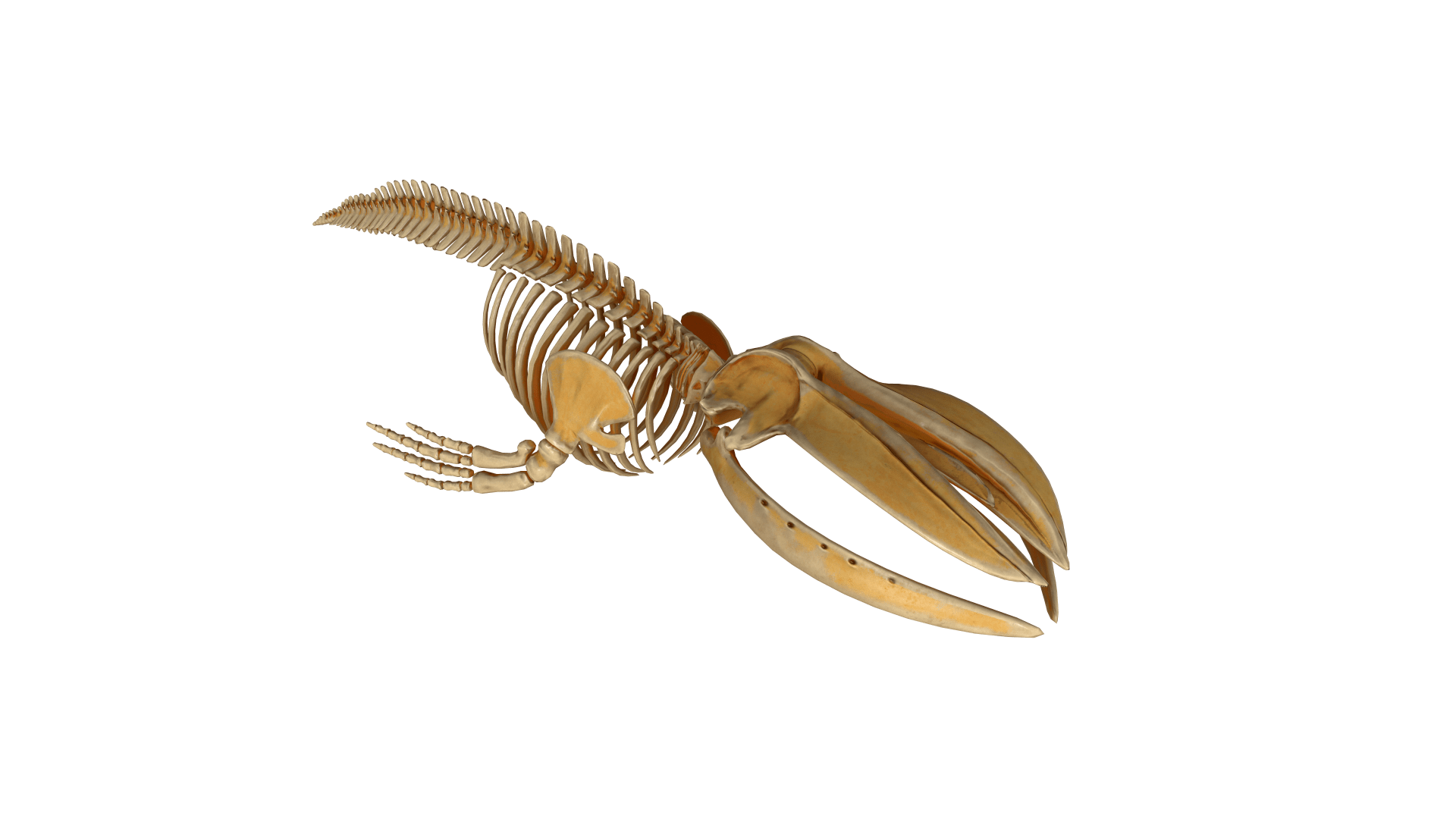

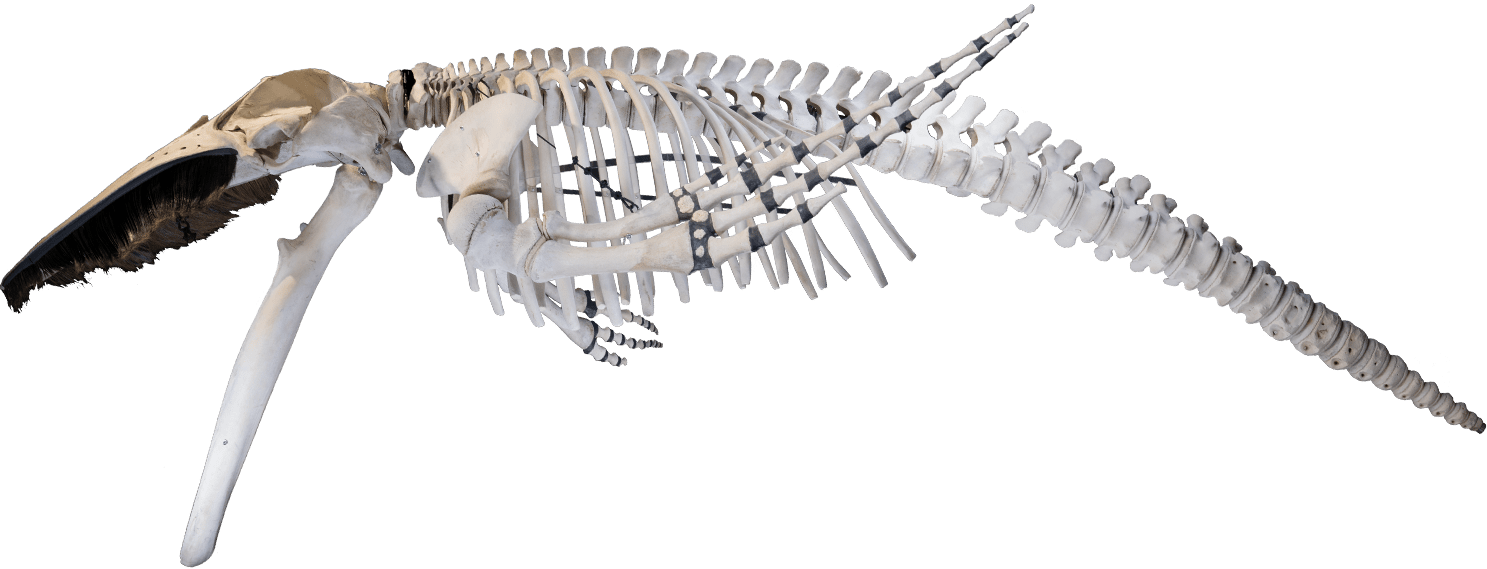

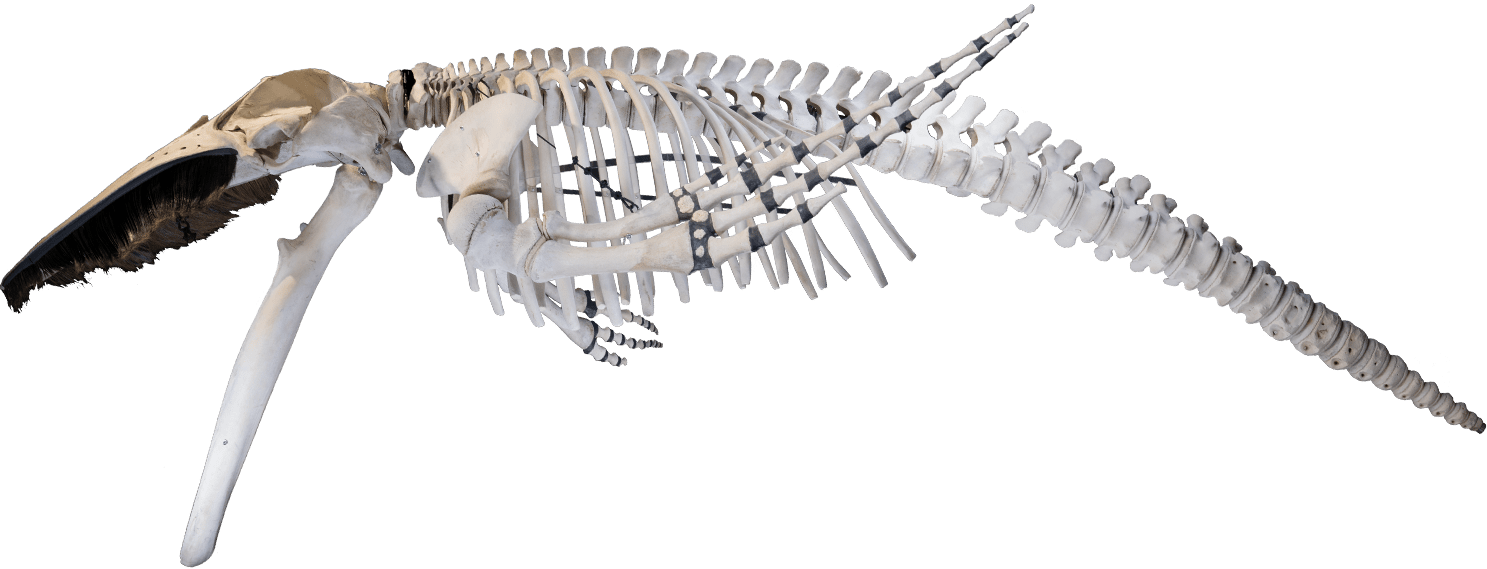

Godbout’s skeleton has been reassembled in a unique position. It was placed in a feeding position, as if the whale were getting ready to close its jaws on a mouthful of food on the water surface. It is one of the most recent skeletons to have been added to the exhibition at the Marine Mammal Interpretation Centre in Tadoussac.

Humpback whale

Megaptera novaeangliae

Characteristics

Northwest Atlantic humpback whales

Weight

30 to 40 tons

Length

13 to 17 m

Lifespan

Environ 80 ans

Population

approx. 12,000 individuals

Status

Not at risk

Godbout

Weight

7.4 tons

Length

9.04 m

Birth - Death

probably 2016 - May 2017

ID number

not known to researchers

Sex

Female

Godbout’s skeleton has been reassembled in a unique position. It was placed in a feeding position, as if the whale were getting ready to close its jaws on a mouthful of food on the water surface. It is one of the most recent skeletons to have been added to the exhibition at the Marine Mammal Interpretation Centre in Tadoussac.